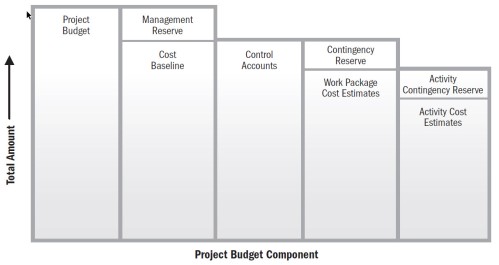

Risk management and Earned Value practitioners, and a range of standards, advocate the inclusion of contingencies in the project baseline to compensate for defined risk events. The contingency may (should) include an appropriate allowance for variability in the estimates modelled using Monte Carlo or similar; these are the ‘known unknowns’. They also advocate creating a management reserve that should be held outside of the project baseline, but within the overall budget to protect the performing organisation from the effects of ‘unknown unknowns’. Following these guidelines, the components of a typical project budget are shown below.

The calculations of contingency reserves should be incorporated into an effective estimating process to determine an appropriate cost estimate for the project[1]. The application of appropriate tools and techniques supported by skilled judgement can arrive at a predictable cost estimate which in turn becomes the cost baseline once the project is approved. The included contingencies are held within the project and are accessed by the project management team through normal risk management processes. In summary, good cost estimating[2] is a well understood (if not always well executed) practice, that combines art and science, and includes the calculation of appropriate contingencies. Setting an appropriate management reserve is an altogether different problem.

Setting a realistic management reserve

Management reserves are an amount of money held outside of the project baseline to ‘protect the performing organisation’ against unexpected cost overruns. The reserves should be designed to compensate for two primary factors. The first are genuine ‘black swans’ the other is estimating errors (including underestimating the levels of contingency needed).

The definition of a ‘black swan’ event is a significant unpredicted and unpredictable event[3]. In his book of the same name, N.N. Taleb defines ‘Black Swans’ as having three distinct characteristics: they are unexpected and unpredictable outliers, they have extreme impacts, and they appear obvious after they have happened. The primary defence against ‘black swans’ is organisational resilience rather than budget allowances but there is nothing wrong with including an allowance for these impacts.

Estimating errors leading to a low-cost baseline, on the other hand, are both normal and predictable; there are several different drivers for this phenomenon most innate to the human condition. The factors leading to the routine underestimating of costs and delivery times, and the over estimating of benefits to be realised, can be explained in terms of optimism bias and strategic misrepresentation. The resulting inaccurate estimates of project costs, benefits, and other impacts are major source of uncertainty in project management – the occurrence is predictable and normal, the degree of error is the unknown variable leading to risk.

The way to manage this component of the management reserves is through the application of reference class forecasting which enhances the accuracy of the budget estimates by basing forecasts on actual performance in a reference class of comparable projects. This approach bypasses both optimism bias and strategic misrepresentation.

Reference class forecasting is based on theories of decision-making in situations of uncertainty and promises more accuracy in forecasts by taking an ‘outside view’ of the projects being estimated. Conventional estimating takes an ‘inside view’ based on the elements of the project being estimated – the project team assesses the elements that make up the project and determine a cost. This ‘inside’ process is essential, but on its own insufficient to achieve a realistic budget. The ‘outside’ view adds to the base estimate based on knowledge about the actual performance of a reference class of comparable projects and resolves to a percentage markup to be added to the estimated price to arrive at a realistic budget. This addition should be used to assess the value of the project (with a corresponding discounting of benefits) during the selection/investment decision making processes[4], and logically should be held in management reserves.

Overcoming bias by simply hoping for an improvement in the estimating practice is not an effective strategy! Prof. Bent Flyvbjerg’s 2006 paper ‘From Nobel Prize to Project Management: Getting Risks Right[5]’ looked at 70 years of data. He found: Forecasts of cost, demand, and other impacts of planned projects have remained constantly and remarkably inaccurate for decades. No improvement in forecasting accuracy seems to have taken place, despite all claims of improved forecasting models, better data, etc. For transportation infrastructure projects, inaccuracy in cost forecasts in constant prices is on average 44.7% for rail, 33.8% for bridges and tunnels, and 20.4% for roads.

The consistency of the error and the bias towards significant underestimating of costs (and a corresponding overestimate of benefits) suggest the root causes of the inaccuracies are psychological and political rather than technical – technical errors should average towards ‘zero’ (plusses balancing out minuses) and should improve over time as industry becomes more capable, whereas there is no imperative for psychological or political factors to change:

- Psychological explanations can account for inaccuracy in terms of optimism bias; that is, a cognitive predisposition found with most people to judge future events in a more positive light than is warranted by actual experience[6].

- Political factors can explain inaccuracy in terms of strategic misrepresentation. When forecasting the outcomes of projects, managers deliberately and strategically overestimate benefits and underestimate costs in order to increase the likelihood that their project will gain approval and funding either ahead of competitors in a portfolio assessment process or by avoiding being perceived as ‘too expensive’ in a public forum – this tendency particularly affects mega-projects such as bids for hosting Olympic Games.

Optimism Bias

Reference class forecasting was originally developed to compensate for the type of cognitive bias that Kahneman and Tversky found in their work on decision-making under uncertainty, which won Kahneman the 2002 Nobel Prize in economics[7]. They demonstrated that:

- Errors of judgment are often systematic and predictable rather than random.

- Many errors of judgment are shared by experts and laypeople alike.

- The errors remain compelling even when one is fully aware of their nature.

Because awareness of a perceptual or cognitive bias does not by itself produce a more accurate perception of reality, any corrective process needs to allow for this.

Strategic Misrepresentation

When strategic misrepresentation is the main cause of inaccuracy, differences between estimated and actual costs and benefits are created by political and organisational pressures, typically to have a business case approved, or a project accepted, or to get on top of issues in the 24-hour news cycle. The Grattan Institute (Australia) has reported that in the last 15 years Australian governments had spent $28 billion more than taxpayers had been led to expect. A key ‘political driver’ for these cost overruns was announcing the project (to feed the 24-hour news cycle) before the project team had properly assessed its costs. While ‘only’ 32% of the projects were announced early, these accounted for 74% of the value of the cost overruns.

The Grattan Institute (Australia) has reported that in the last 15 years Australian governments had spent $28 billion more than taxpayers had been led to expect on transport infrastructure projects. One of the key ‘political drivers’ for these cost overruns was announcing the project (to feed the 24-hour news cycle) before the project team had properly assessed its costs. While ‘only’ 32% of the projects were announced early, these projects accounted for 74% of the value of the cost overruns.

Reference class forecasting will still improve accuracy in these circumstances, but the managers and estimators may not be interested in this outcome because the inaccuracy is deliberate. Biased forecasts serve their strategic purpose and overrides their commitment to accuracy and truth; consequently the application of reference class forecasting needs strong support from the organisation’s overall governance functions.

Applying Reference Class Forecasting

Reference class forecasting does not try to forecast specific uncertain events that will affect a particular project, but instead places the project in a statistical distribution of outcomes from the class of reference projects. For any particular project it requires the following three steps:

- Identification of a relevant reference class of past, similar projects. The reference class must be broad enough to be statistically meaningful, but narrow enough to be truly comparable with the specific project – good data is essential.

- Establishing a probability distribution for the selected reference class. This requires access to credible, empirical data for a sufficient number of projects within the reference class to make statistically meaningful conclusions.

- Comparing the specific project with the reference class distribution, in order to establish the most likely outcome for the specific project.

The UK government (Dept. of Treasury) were early users of reference class forecasting and continue its practice. A study in 2002 by Mott MacDonald for Treasury found over the previous 20 years on government projects the average works duration was underestimated by 17%, CAPEX was underestimated by 47%, and OPEX was underestimated by 41%. There was also a small shortfall in benefits realised.

This study fed into the updating of the Treasury’s ‘Green Book’ in 2003, which is still the standard reference in this area. The Treasury’s Supplementary Green Book Guidance: Optimism Bias[8] provides the recommended range of markups with a requirement for the ‘upper bound’ to be used in the first instance by project or program assessors.

These are very large markups to shift from an estimate to a likely cost and are related to the UK government’s estimating (ie, the client’s view), not the final contractors’ estimates – errors of this size would bankrupt most contractors. However, Gartner and most other authorities routinely state project and programs overrun costs and time estimates (particularly internal projects and programs) and the reported ‘failure rates’ and overruns have remained relatively stable over extended periods.

Conclusion

Organisations can choose to treat each of their project failures as a ‘unique one-off’ occurrence (another manifestation of optimism bias) or learn from the past and develop their own framework for reference class forecasting. The markups don’t need to be included in the cost baseline (the project’s estimates are their estimates and they should attempt to deliver as promised); but they should be included in assessment process for approving projects and the management reserves held outside of the baseline to protect the organisation from the effects of both optimism bias and strategic misrepresentation. As systems, and particularly business cases, improve the reference class adjustments should reduce but they are never likely to reduce to zero, optimism is an innate characteristic of most people and political pressures are a normal part of business.

If this post has sparked your interest, I recommend exploring the UK information to develop a process that works in your organisation: http://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-green-book-appraisal-and-evaluation-in-central-governent

______________________

[1] For more on risk assessment see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1015_Risk_Assessment.pdf

[2] For more on cost estimating see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1051_Cost_Estimating.pdf

[3] For more on ‘black swans’ see: /2011/02/11/black-swan-risks/

[4] For more on portfolio management see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1017_Portfolios.pdf

[5] Project Management Journal, August 2006.

[6] For more on the effects of bias see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1069_Bias.pdf

[7] Kahneman, D. (1994). New challenges to the rationality assumption. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical

Economics, 150, 18–36.

[8] Green Book documents can be downloaded from: http://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-green-book-appraisal-and-evaluation-in-central-governent