Numerous studies have consistently shown that organisations that support overt corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, either by allowing staff to participate in voluntary work or by donating to charities, or 100s of similar options for giving back to the wider community do better than organisations that do not. It is an established fact that organisations that embrace CSR have a better bottom line and more sustained growth, however, what has not been clear from the various studies is why!

Two options regularly canvassed are:

- Because the organisation is doing well for other reasons it has the capacity to donate some of the surplus it is generating to the wider community whereas organisations that are not doing so well need to conserve all of their resources. Factor in the effect of taxation and great PR is generated at a relatively low net cost.

- Because the organisation does ‘CSR’ it enhances its reputation and as a consequence becomes a more desirable place to work and therefore attracts better staff at lower costs and is also seen as a better organisation to ‘do business with’ and therefore attracts better long term partners and customers again at a lower cost than other forms of ‘public relations’ and advertising.

Both of these factors have a degree of truth about them and frankly, if an organisation does not seek to maximise any competitive advantage its management are failing in their duties. However, this post is going to suggest these are welcome collateral benefits and the reason CSR is associated with high performance organisations lays much deeper.

We suggest that observable CSR is a measurable symptom of ‘good governance’. The Chartered Institute of Internal Auditors define governance in the following terms:

Governance is about direction, structure, process and control, it also is about the behaviour of the people who own and represent the organisation and the relationship that the organisation has with society. Key elements of good corporate governance therefore include honesty and integrity, transparency and openness, responsibility and accountability.

Consequently, a well governed organisation will generally have a good reputation in the wider community; this is the result of the organisation’s stakeholders giving that organisation credibility and loyalty, trusting that the organisation makes decisions with the good of all stakeholders in mind. It can be summarised as the existence of a: a general attitude towards the organisation reflecting people’s opinions as to whether it is substantially ‘good’ or ‘bad’. And this attitude is connected to and impacts on the behaviour of stakeholders towards the organisation which affects the cost of doing business and ultimately the organisation’s financial performance.

Therefore, if one accepts the concept that the primary purpose of an organisation of any type is to create sustainable value for its stakeholders and that a favourable reputation is a key contributor to the organisation’s ability to create sustainable value. The importance of having a ‘favourable reputation’ becomes apparent, the reputation affects stakeholder perceptions which influence the way they interact with the business – and a favourable reputation reduces the cost of ‘doing business’.

However, whilst a well governed organisation needs, and should seek to nurture this favourable reputation, it is not possible to generate a reputation directly. The organisation’s reputation is created and exists solely within the minds of its stakeholders.

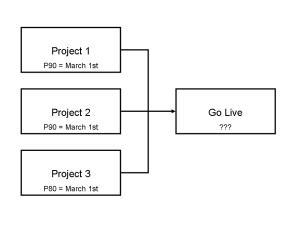

As the diagram below suggests, what is needed and how it is created work in opposite directions!

What the organisation needs is a ‘favourable reputation’ because this influences stakeholder perceptions which in turn improve the stakeholder’s interaction with the organisation, particularly as customers or suppliers which has a demonstrated benefit on the cost of doing business. But an organisation cannot arbitrarily decide what its reputation will be.

An organisation’s ‘real reputation’ is not a function of advertising, it is a function of the opinions held by thousands, if not millions of individual stakeholders fed by all of the diverse interactions, communications, social media comments and other exchanges stakeholders have with other stakeholders. Through this process of communication and reflection the perception of a reputation is developed and stored in each individual’s mind. No two perceptions are likely to be exactly the same, but a valuable ‘weight of opinion’ will emerge for any organisation over time. The relevant group of stakeholders important to the business will determine for themselves if the organisation is substantially ‘good’ or ‘bad’. And because the sheer number of stakeholder-to-stakeholder interactions once an opinion is generally ‘held’, it is very difficult to change.

The art of governance is firstly to determine the reputation the organisation is seeking to establish, and then to create the framework within which management decisions and actions will facilitate the organisation’s interaction with its wider stakeholder community, consistent with the organisations communicated objectives.

Authenticity is critical and ‘actions speak louder than words’ – it does not matter how elegant the company policy is regarding its intention to be the organisation of choice, for people to work at, sacking 500 people to protect profits tells everyone:

- The organisation places short term profits ahead of people.

- The organisations communications are not to be trusted.

The way a valuable reputation is created is through the various actions of the organisation and the way the organisation engages with its wider stakeholder community. Experiencing these interactions create perceptions in the minds of the affected stakeholders about the organisation. These perceptions are reinforced by stakeholder-to-stakeholder communication (consistency helps), and the aggregate ‘weight’ of these perceptions generates the reputation.

The role of CSR within this overall framework is probably less important that the surveys suggest. Most telecommunication companies spend significant amounts on CSR but also have highly complex contracts that frequently end up costing their users substantial sums. Most people if they feel ‘ripped off’ are going to weight their personal pain well ahead of any positives from an observed CSR contribution and tell their friends about their ‘bad’ perception.

However, as already demonstrated, actions really do speak louder than words – most of an organisation’s reputation will be based on the actual experiences of a wide range of stakeholders and what they tell other stakeholders about their experiences and interactions. Starting at Board level with governance policies that focus on all of the key stakeholder constituencies including suppliers, customers, employees and the wider community is a start. Then backing up the policy with effective employment, surveillance and assurance systems to ensure the organisation generally ‘does good’ and treats all of its stakeholders well and you are well on the way. Then from within this base, CSR will tend to emerge naturally and if managed properly becomes the ‘icing on the cake’.

In short, genuine and sustained CSR is a symptom of good governance and a caring organisation that is simply ‘good to do business with’.

Unfortunately, the current focus on CSR will undoubtedly tempt organisations to treat CSR as just another form of advertising expenditure and if enough money is invested it may have a short term effect on the organisation’s reputation – but if it’s not genuine it won’t last.

One resource to help organisations start on the road to a sustainable culture of CSR is ISO 26000: 2010 – Social responsibility. The Standard helps clarify what social responsibility is, helps businesses and organisations translate principles into effective actions and shares best practices relating to social responsibility. This is achieved by providing guidance on how businesses and organisations can operate in a socially responsible way which is defined as acting in an ethical and transparent way that contributes to the health and welfare of society. Figure 1 provides an overview of ISO 26000.

Interestingly, my view that understanding who the organisation’s stakeholders really are and engaging with them effectively is the key to success, is also seen as crucial by the standard developers! For more on stakeholder mapping see: http://www.stakeholdermapping.com

Conclusion

This has grown into a rather long post! But the message is simple: Effective CSR is a welcome symptom of an organisation that understands, and cares about its stakeholders and this type of organisation tends to be more successful than those that don’t!