Project Management 2.0 (PM 2.0) seems to be going the same way some Agile anarchists are trying to take software development which is essentially not to do project management and hope a group of people with good will and good luck will create something useful.

Not doing ‘project management’ is a really good idea if you and your client have no idea what’s needed, when its required, or how much budget is available. Journeys of exploration can be fun and can be highly creative but are nothing to do with managing projects.

Wikipedia (retrieved 27/9/2009 from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_management_2.0) lists the following differences between PM 2.0 and ‘traditional’ project management.

PM 2.0 -v- Traditional PM

Whoever wrote this has absolutely no idea what good traditional project management looks like and has probably never worked on a successful major project. Good traditional project management differs from this highly subjective and biased list in many ways:

- Control is not centralised, authority and responsibility are devolved to the appropriate management levels.

- All good project management is based on collaboration.

- All good project management requires open access to the plan both as an input to its creation and to know what needs doing during delivery.

- Access to information is vial when and where needed.

- Open and effective communication is critical.

- Project are, by definition, separate management entities – a holistic approach (ie, not doing projects) is called general management.

- Tools, see: A fool with a tool is still a fool, and you need the right tools for the right job. Amateurs try to do jobs with inappropriate tools. Easy to use and flexible are fine if you know exactly what you are doing, it is a recipe for wrong information and wrong decisions if you don’t.

The table is correct in so much as project management involves a degree of top down planning. Project management is about delivering a required output to the specifications requested by the client. The product or service is a failure if it does not meet the quality requirements set by the customer; which may include time, cost and scope parameters.

It is also correct in respect of the implied structure – projects work because there is an implied structure that sets a framework for collaboration. If you don’t know who is doing what it is nearly impossible to collaborate. Even Wikipedia and Linux have structure in their collaborative frameworks.

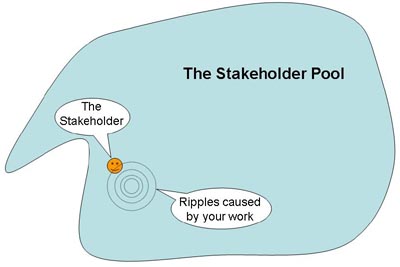

I have emphasised good project management throughout this post. Bad project management involves excessive attempts to ‘control the future’, lack of stakeholder involvement, excessive bureaucracy, and many other problems. These traits are bad management full stop.

One comment on the Wikipedia article is important though: PM 2.0 is good for small jobs. This is consistent with a survey of construction projects in the UK undertaken by the Chartered Institute of Building, focused on time management, which found that on ‘simple projects’ there was no difference in performance between those projects with a properly developed and managed schedule and those without. The same proportions finished early, on time and late.

However, as soon as the projects became ‘complex’; there was a marked difference in performance. Projects with effective schedule control performed significantly better than those without, and the bigger/more complex the project, the more significant the difference. ( I will put up a post on the CIOB’s work and its new practice standard for scheduling in a few days).

The CIOB’s findings and a closer look at many of the blogs and comments on both PM 2.0 and Agile seem to fit this trend. I would suggest two conclusions could be drawn:

- If the work is small, simple and easy to understand there is no need for much in the way of traditional project controls. Knowledgeable people know what needs to be done and can just get on with the work.

- If the required output is not capable of being determined by the client and the objective is to ‘create something wonderful’ it is very difficult to apply too many project management techniques – basically you don’t know what needs to be planned, costed and scheduled, etc. Time and cost are secondary to creativity and the exploration of problems.

In both of these circumstances traditional project management may not be appropriate. In fact I would question if either circumstance is actually a project given the definition of a project is to produce a defined product, service or result that meets the needs of a customer.

The challenge for senior organisational management is recognising the threshold where PM 2.0 and ‘free form Agile’ cease to be appropriate and more traditional forms of project management are needed. Traditional project management does not mean ridged control, the type of project influences what’s needed (see: Projects aren’t projects – Typology) but appropriate systems do help optimize cost, time and quality to deliver client satisfaction.

This does not mean dumping the new ideas, rather melding them into an improved project management process. Agile software development fits in nicely to ‘rolling wave’ planning. Similarly some aspects of PM 2.0 can really help enhance team communication and collaboration. Used wisely, these ideas and technologies simply help improve the way projects work to deliver quality outputs to their clients. This change is really no different to the shift from faxes and carbon copy paper to emails. Good project management has always adapted to use improvements in processes and technology to improve the quality of service provided to the project’s clients. This next wave of improved technologies should be no different.

However, be wary of the zealots suggesting the ‘old ways’ don’t work and should be abandoned and use examples of really bad project management to prove their point. This is even more important if the zealots also advocate employing them to solve all of your problems for a fee. Management fads come and go – modern project management has been generally successful in achieving positive outcomes for well over 50 years now and continues to evolve and improve. For further comment see Glen’s post on: Herding Cats