The Port of Melbourne is the largest port for containerized and general cargo in Australia. Anyone visiting the port, or Melbourne generally, would think the Yarra River must have been a useful harbor at the time of settlement, and the various docks were built to enhance this natural asset. Modern maps, and the view out to Port Philip Bay reinforce this concept.

The truth is very different, almost everything shown in the pictures above is man made.

Settlement

The settlement of Melbourne started in 1835. To put this date in context, it is 20 years after the Battle of Waterloo and 2 years before the coronation of Queen Victoria[1]. The original settlement was located in the area of the current day CBD. This site was chosen for its access to fresh water from the stream running through the site, rather than its potential as a port.

https://www.ecocentre.com/programs/community-programs/indigenous/

Early problems

An underwater sand bar at the entrance of the Yarra River ruled out the entry of vessels drawing more than about nine feet of water and access up river was blocked at ‘The Falls’, a rock bar running across the river which was used as a crossing point by the local Aboriginal peoples.

This limited access meant ships arriving from overseas had to drop anchor in Hobson’s Bay, or moor at the Sandridge (Port Melbourne) Pier. Passengers and goods then had to walk, use carts, or be transshipped up the river in smaller vessels or ‘lighters’ as they were called. Costs were excessive! It has been recorded that it cost 30 shillings per ton (half the entire freight costs for the voyage from England) to have goods taken the eight miles from sea to city.

The discovery of gold in 1850 exacerbated the problems of the port. In just one week in 1853 nearly 4000 passengers from 138 ships arrived in Hobson’s Bay and in 1858 the average delay moving goods from the port into the city was three weeks.

The initial solution to this problem was the construction in 1854 of the first steam railway in Australia from piers built at Sandridge (now the suburb of Port Melbourne) to the city this railway is discussed in The First Steam Powered Railway in Australia, but a better solution was needed for cargo.

Developing the Port of Melbourne – 1839 to 1877

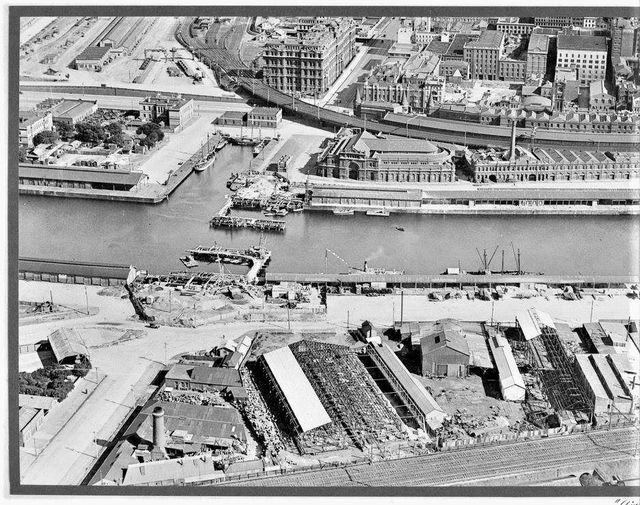

The Yarra River was progressively improved to facilitate trade. Jetties were built along the banks of the river from 1839 onwards funded by wharfage charges. This 1857 photograph shows the wharfs downstream from ‘The Falls’.

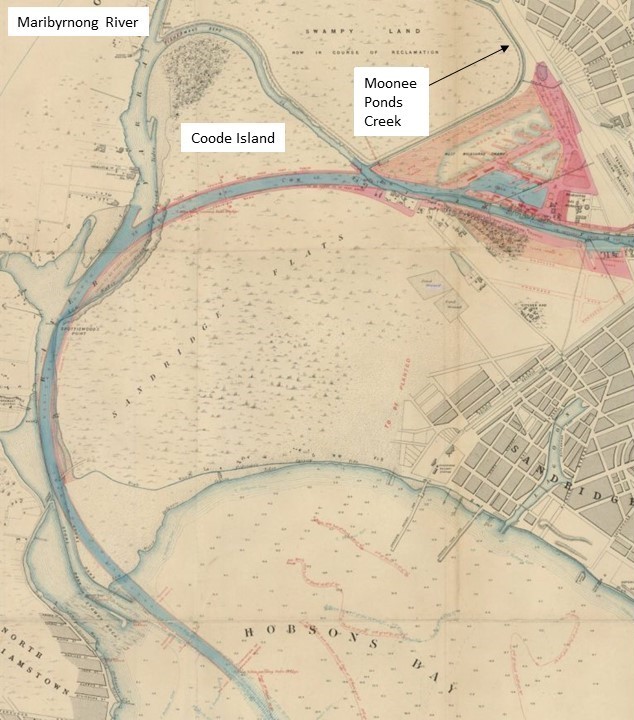

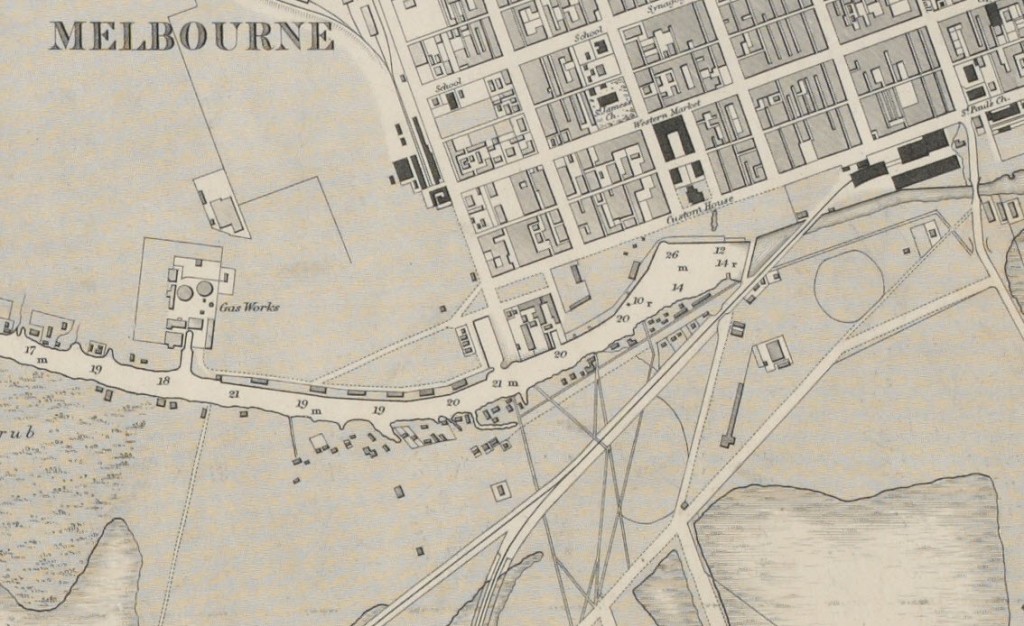

The 1864 map of Melbourne shows the limitations outlined above were still limiting the development of Melbourne despite the massive influx of money from the Victorian gold rush. The Falls effectively dammed the river causing major flooding and the restrictions caused by the swamps bends and shoals in the Yarra restricted trade.

https://mosaicprojects.com.au/PDF-Gen/Melbourne_1864.jpg

Developing the Port of Melbourne – 1877 to 1902

To overcome the problems, the Melbourne Harbor Trust was formed in 1877 and engaged English engineer, Sir John Coode to recommend solutions.

Starting in 1879 Sir John Coode made three key recommendations:

– the development of a canal to improve access for ships,

– the demolition of The Falls to reduce flooding, and

– the deepening of the narrow entrance to Port Phillip Bay from the ocean.

Based on Sir John’s recommendation, the course of the lower Yarra’s was significantly altered. This visionary feat of engineering involved 2,000 workers for 20 years. The proposal not only significantly shortened travel time up the river for ships, but also created Victoria Harbour and Victoria Dock.

The original wide loop in the river was eliminated through the construction of the 1.5 km Coode Canal which opened in 1886, and West Melbourne Dock (now Victoria Dock) opened to shipping in 1893. The canal created Coode Island and caused the shallow, narrow and winding Fishermans Bend to be cut off along with other sections of the river including Humbug Reach and the original junction with the Maribyrnong River. The Coode Canal was deepened to 25 feet and widened from 100 to 145 feet in 1902.

The plan to remove ‘The Falls’ involved clearing the reef to a uniform depth of 15 feet 6 inches, at an estimate cost of £20,000. The demolition was complete by 1883, having been funded by a combination of the Victorian Government and the Harbour Trust. The reduction in flooding caused by the improved river flows converted flood plains and swamps into dry land, encouraging the development of South Melbourne discussed in The evolution of South Melbourne. The lake in Albert Park is all that remains of the freshwater lagoons and seasonal swamps South of the Yarra.

The Rip at Port Phillip Heads was also deepened in 1883 using explosives.

Developing the Port of Melbourne – 1902 onward.

The piers at Sandridge (Port Melbourne) continued to be important, but mainly for passengers. A new pier, built to the west of Railway Pier, opened in 1916, called the New Railway Pier. This was renamed Prince’s Pier in 1921. These piers were important locations for the departure and return of troops to the Boer War in South Africa and WW1 &2, as well as the arrival of many thousands of migrants after WW2.

The current Station Pier, which replaced the original Railway Pier, was built between 1922 and 1930 and remains the primary passenger arrival point in Melbourne with cruise ships visiting throughout summer. Princes Pier has been demolished.

Meanwhile, most cargo shipments were handled by the Victoria Dock, and by 1908 it was handling ninety per cent of Victoria’s imports. In 1914 its capacity was enlarged by the addition of a central pier and in 1925 the entrance was widened. But with rapidly increasing imports and exports further renovation and development was needed. Also, as ships increased in size there was a need for larger wharves and deeper berths to accommodate them.

The growth of the city also encroached on the Eastern end of the docks. The construction of the Spencer Street Bridge in 1927-28 meant that all port traffic had to be handled further downstream, foreshadowing the need for even more docks, and the expansion of the port towards the West and the bay.

To overcome these challenges, the docks spread to the West, and no cover all of the land between the land from Moonee Ponds Creek to the Maribyrnong River, totally absorbing Coode Island.

The original Victoria Dock and the adjacent North Wharf on the river continued to play a vital role, handling up to half of the Port of Melbourne’s trade until the shift to containerisation and then the construction of the Bolte Bridge in 1999, made the old port facilities redundant. From 2000 the Victoria Docks became Docklands, and were revitalised as commercial and residential areas, while the Port of Melbourne continues to expand downstream.

The last major expansion of the port was the construction of Webb Dock at the mouth of the Yarra River in 1960.

Improvements in both wharf-side and land-side facilities continue, but despite all of these improvements, the Port of Melbourne is approaching capacity, the next developments are not far off but need political decisions on the location, either in Port Phillip Bay or Westernport Bay to allow the next transformation to start.

Footnote on the names

The rock bar called ‘The Falls’ in this post was called Yarro- Yarro meaning “waterfall or ever flowing” by the local peoples. The river was known as the Birrarung by the Wurundjeri people. The first settlers confused the names and called the river Yarra.

The , Yarro Yarro Falls were important to the local Aboriginal tribes, the Woiwurrung and the Boonerwrung, who used it as a crossing point between their lands, in order to negotiate trade and marriages. This was the only means of crossing the Yarra River until ferries and punts began operating c 1838. The first bridge was constructed c 1845, a little further upstream, at the location very near what is now known as the ‘Princes Bridge’.

For more papers on the history of the construction industry see:

https://mosaicprojects.com.au/PMKI-ZSY-005.php#Bld

[1] A historical timeline can be viewed at: https://mosaicprojects.com.au/PDF_Papers/P212_Historical_Timeline.pdf