Last week I participated in two PUXX panel discussions in Perth and Sydney focused on predicting the influence of technology on project controls. The range of subjects covered ranged from drones and remote monitoring to virtual reality.

Many of the topics discussed offered better ways to do things we already do, provided we can make effective use of the data generated in ever increasing quantities – significant improvements but essentially ‘business-as-usual’ done better. The aspect I want to focus on in this post is the potential to completely reframe the way project schedules are developed and controlled when existing ‘gaming technology’ and BIM are synthesised.

The current paradigm used for critical path scheduling is a (dumbed-down) solution to a complex set of problems required to allow the software to run on primitive mainframe computers in the late 1950s – the fundamentals have not changed since! See: A Brief History of Scheduling.

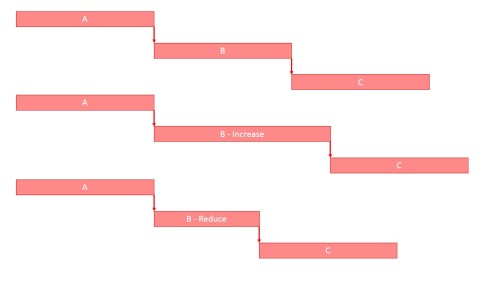

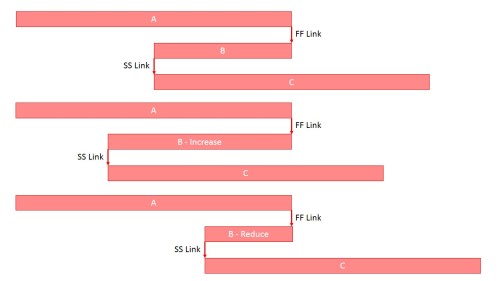

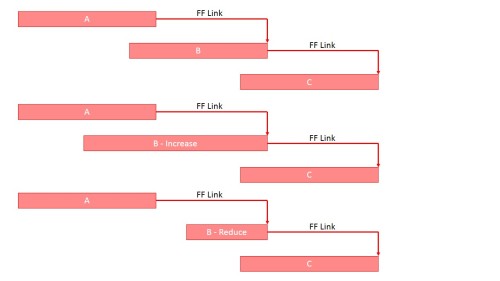

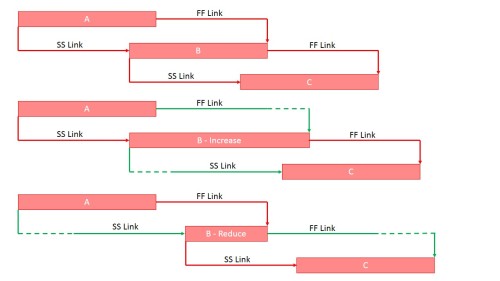

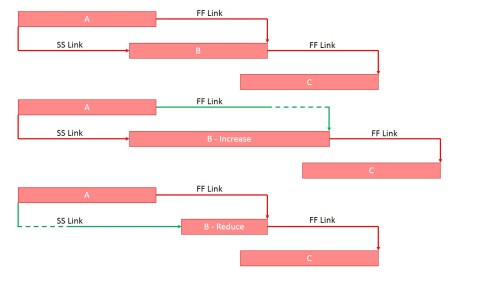

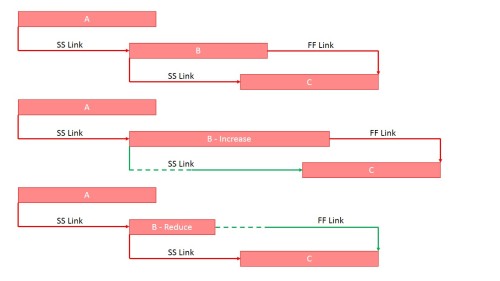

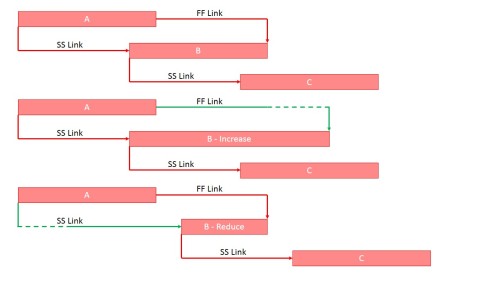

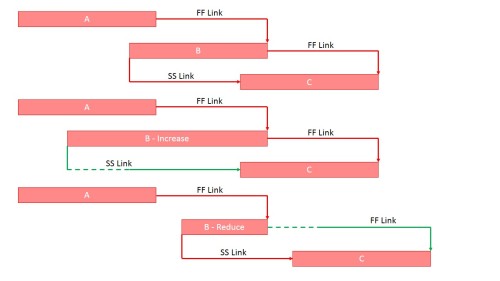

The underlying assumption is a project consists of a set of activities each with a defined duration and depending on the logical relationship between the activities, some are ‘critical’ others have ‘float’. The basic flaw in this approach can be demonstrated by looking at the various options open to a schedule to define the work involved in 3 simple foundations involving excavation and mass concrete fill.

All four of the above options above are viable alternatives that may be chosen by different schedulers to describe the work using CPM, and none of them really describe what actually happens. The addition of more links would help but even then the real situation which is one resource crew visits three locations in turn and excavates the foundations, a second crew follows and places the concrete with some options for overlapping, parallel working and possibly synchronising the actual pouring of all three foundations on the same day…….. Optimising the work of the crews is the key to a cost effective outcome and this depends on what follows their work. For more on resource optimisation see: www.mosaicprojects.com.au/Resources_Papers_152.html. Advances in computer software offer the opportunity to develop a new way of working.

The starting point for the hypothesis outlined I this post is 4D BIM (Building Information Modelling). Last month I was in London working on the final edits to the second edition of the CIOB’s book, Guide to Good Practice in the Management of Time in Complex Projects (due for publication in 2017 as The Management of Time in Major Projects). One of the enhancements in the second edition is an increased focus on BIM. To assist our work a demonstration of cutting edge 4D BIM was provided Freeform.

Their current capabilities include:

- The ability to model in real time clashes in working space provided the space needed for each crews work is parameterised. Change the timing of one work crew and the effect on others in a space is highlighted.

- The ability to view the work from any position at any time in the construction process; allowing things such as a tower crane driver’s actual line of sight to be literally ‘seen’ at different stages of the construction.

- The relatively normal ability to import schedule timings from a range of standard tools to animate the building of the model, and the ability to feedback information derived from processes such as the identification of clashes in the use of working space using

- The space occupied by temporary works and various pieces of equipment can be defined and clashes with permanent works identified over time.

- Finally the ability for a person to see and move around within the virtual model using the same type of 3D virtual reality goggles used by many gaming programmes. The wearer is literally immersed in the model.

For all of this in action on a major rail project see: https://www.newcivilengineer.com/future-tech/pushing-the-limits-of-bim/10012298.article

Moving into the world of game playing, there are many different games that allow players in competition, or collaboration, to ‘build’ cities, empires, fortifications, farms, etc. These games know the resources available to the players and how many resources will be required to construct each new element in the game – if you don’t have the resources, you can’t build the new asset.

Combining these two concepts opens up the possibility for a completely new approach to scheduling physical projects that involve the deployment of resources to physical locations to undertake work. The concept of location-based scheduling is not new, it was used in the 1930s to construct the Empire State Building (see: Line of Balance) and is still widely used. For more on location-based scheduling see: Location-Based Management for Construction: Planning, Scheduling, and Control by Prof. Russell Kenley.

How these concepts tie into BIM starts with the model itself. A BIM model consists of a series of parameterised objects. Each object can contain data on its size, weight, durability, cost, maintainability, carbon footprint, etc. As BIM develops many of these objects will come from standard libraries created by suppliers and subcontractors. Change an object, for example, replace windows from manufacturer “A” with similar Windows from manufacturer “B” and the model is update and potential issues with sizes, fixings and waterproofing can be identified. It is only a small step from this point to add parameters related to the resources needed to undertake the work of installation.

With this information and relatively minor enhancements to current BIM capabilities, once the engineering model is reasonably complete a whole new paradigm for planning work opens up.

To plan the work the ‘planning team’ put on their virtual reality headsets and literally ‘walk’ onto the site. As they start to locate temporary works and begin the building process the model is tracking the use of resources and physical space in real time. The plan is developed based on the embedded parameters in the fully integrated 3D model.

Current 4D imports a schedule ‘shows you’ the effect. Using the proposed gaming approach and parameterized objects you can literally build the project in the virtual space and either see the consequences on resource loading or be limited by resource availability. A whole bunch of games do this already, add in existing clash detection capabilities (but applied to workers using the space) and you change the whole focus of planning a project. Decisions can be made to adjust the size of resource crews and the flow of work can be optimised to balance the competing objectives of cost efficiency, time efficiency and resource optimisation.

The proposed model is a paradigm shift away from CPM and its arbitrary determination of activities and durations to a process focused on the smooth flow of resources through work areas. The computational base will be focused on resource effectiveness and resource utilisation. Change ‘critical path’ to ‘critical resources’, eliminate the illusion of ‘float’ but look for underutilised resources and resource waiting time. To optimise the work, different scenarios can be stored, replayed and edited – the ultimate ‘what-if’ experience.

The concept of ‘schedule density‘ ties in with this approach nicely; initial planning is done for the whole project at the ‘low density’ level with activity durations of several weeks or months setting out the overall ‘time budget’ for the project and establishing the strategic flow of work. As the design improves and more information becomes available, the schedule is enhanced first to ‘medium density’ and then to ‘high density’. The actual work is controlled by the ‘high density’ part of the schedule. For more on ‘schedule density’ see: www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1016_Schedule_Density.pdf.

Where this concept gets really interesting is in the control of the work. The medium and high density elements of the schedule are built using the same ‘virtual reality’ process as the overall schedule, therefore each object in the overall BIM model can include data on the resources allocated to the work, the sequence of work and the time allowed. Given workers on BIM-enabled projects already use various PDAs to access details of their work, the same tablet or smart device can be used to tell the workers their next job and how long that have to complete it. When they complete the task, updating the BIM model with that progress information updates the schedule, tells the crew their next job and tells the next resources planned to move into the area that the space is available. The schedule and the 3D model are the same entity.

Similarly, off-site manufacturing and design lead-times can be integrated into the dataset. Each manufactured item can have its design, manufacture and transport and approval times associated with the element making the development of an off-site works / procurement schedule a simple process to extract the report once the schedule is set. Identifying delays in the supply chain and dealing with changes in the timing of installation become staigtforward.

When inevitable problems occur, the project management team have the ideal tool to work through solutions and determine the optimum way forward, as soon as the new schedule is agreed, the BIM model already holds the information.

One of the key concepts in ‘schedule density’ is that any work planned for the short-term future has to be based on the actual performance of the crews doing the work. In a BIM enabled scheduling system this can also be automated. The work content of each activity is held in the model as is the crew assigned to the work. As soon as the work crew’s productivity can be measured, the benchmark values used in the original planning can be updated with real data. Where changes in performance are needed to deal with slippages and productivity issues these can be properly planned and incorporated into the schedule based on when the implemented changes can be expected to occur.

I’m not sure if this is BIM2 or BIM++ but these ideas are not very far in advance of current capabilities – all we need now is a software developer to take on the ideas and make them work.

These concepts will be harder to apply to ‘soft projects’ but the planning paradigms in soft projects have already been shaken up by Agile. But integrating 3D modelling with an integrated capability for real 4D interaction certainly seem to make sense for projects where the primary time management issue is the flow of resources in the correct sequence through a defined series of work locations in three dimensions. What do you think???