The definition of a schedule ‘critical path’ varies (see Defining the Critical Path), but the essence of all of the valid definitions is the ‘critical path’ determines the minimum time needed to complete the project and either by implication or overtly the definitions state that delaying an activity on the critical path will cause a delay to the completion of the project and accelerating an activity will (subject to float on other paths[1]) accelerate the completion of the project.

A series of blog posts by Miklos Hajdu, Research Fellow at Budapest University of Technology and Economics, published earlier this year highlights the error in this assumption and significantly enhances the basic information contained in my materials on ‘Links, Lags and Ladders’ and our current PMI-SP course notes. The purpose of this post is to consolidate all these concepts into a single publication.

The best definition of a critical path is Critical Path: sequence of activities that determine the earliest possible completion date for the project or phase[2]. This definition is always correct. Furthermore, in simple Precedence networks (PDM) that only use Finish-to-Start links, and traditional Activity-on-Arrow (ADM) networks the general assumption that increasing the duration of an activity on the critical path delays the completion of the schedule and reducing the duration of an activity on the critical path accelerates the completion of the schedule holds true. The problems occur in PDM schedules using more sophisticated link types. Miklos has defined five constructs using standard PDM links in which the normal assumption outlined above fails. These constructs, starting with the ‘normal critical’ that behaves as expected are shown diagrammatically below[3].

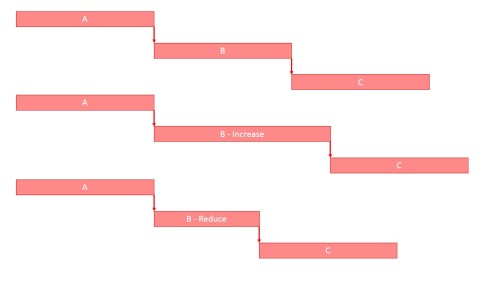

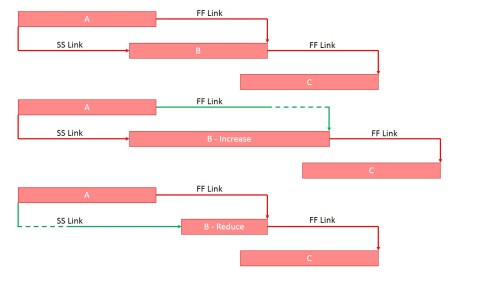

Normal Critical

The overall project duration responds as expected to a change in the activity duration.

A one day reduction of the duration of an activity on the critical path will shorten the project duration by one day, a one day increase will lengthen the project duration by one day.

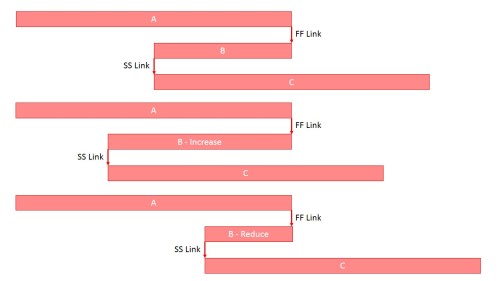

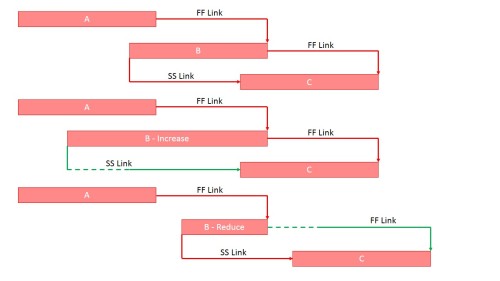

Reverse Critical

The change in the overall project duration is the opposite of any change in the activity duration.

A one day reduction of the duration of Activity B will lengthen the project duration by one day, a one day increase will reduce the project duration by one day.

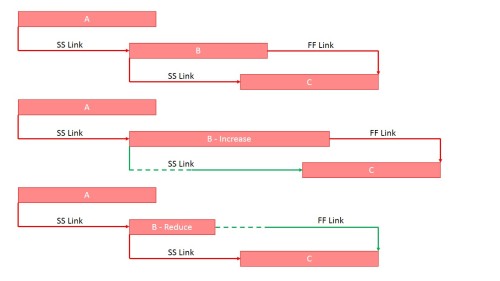

Neutral Critical

Either a day decrease or a day increase leaves the project duration unaffected. There are two variants, SS and FF:

In both cases it does not matter what change you make to Activity B, there is no change in the overall duration of the project. This is one of the primary reasons almost every scheduling standard requires a link from a predecessor into the start of every activity and a link from the end of the activity to a successor.

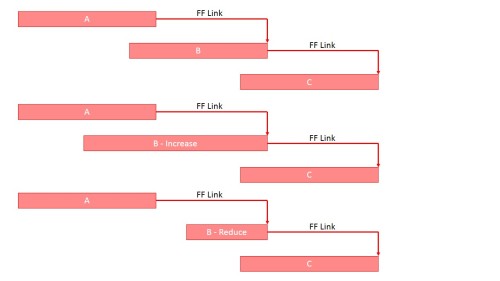

Bi-critical Activities

Any change in the duration of Activity B will cause the project duration to increase.

A one day reduction of the duration of Activity B will lengthen the project duration by one day, a one day increase will lengthen the project duration by one day. Bi-critical activities depend on having a balanced ladder where all of the links and activities are critical in the baseline schedule. Increasing the duration of B pushes the completion of C through the FF link. Reducing the duration of B ‘pulls’ the SS link back to a later time and therefore delays the start of C. The same effect will occur if the ladder is unbalanced or there is some float across the whole ladder, it is just not as obvious and may not flow through to a delay depending on the float values and the extent of the change.

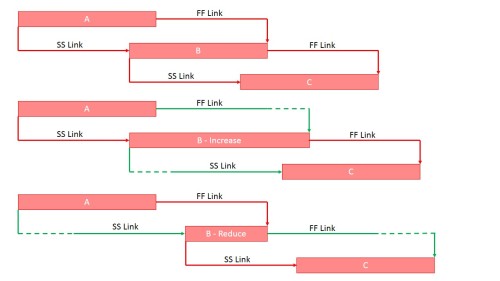

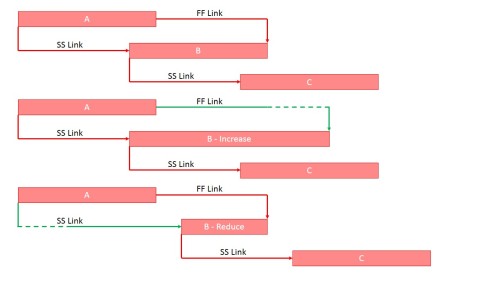

Increasing Normal Decreasing Neutral

An increase in Activity B will delay completion, but a reduction has no effect! There are two variations on this type of construct.

A one day increase in the duration of Activity B will increase the project duration by one day, however, reducing the length of Activity B has no effect on the project’s duration.

Increasing Neutral Decreasing Reverse

An increase in Activity B has no effect, but a reduction will delay completion! Again, there are two variations on this type of construct.

A one day increase in the duration of Activity B has no effect on the project’s duration, however, reducing the length of Activity B by one day will increase the project duration by one day.

Why does this matter?

The concept of the schedule model accurately reflecting the work of the project to support decision making during the course of the work and for the forensic assessment of claims after the project has completed, is central to the concepts of modern project management. Apart from the ‘normal critical’ construct, all of the other constructs outlined above will produce wrong information or allow a claim to be dismissed based on the nuances of the model rather than the real effect.

Using most contemporary tools, all the planner can do is be aware of the issues and avoid creating the constructs that cause issues. Medium term, there is a need to revisit the whole function of overlapping activities in a PDM network to allow overlapping and progressive feed to function efficiently. This problem was solved in some of the old ADM scheduling tools, ICL VME PERT had a sophisticated ‘ladder’ construct[4]. Similar capabilities are available in some modern scheduling tools that have the capability to model a ‘Continuous precedence relationship[5]’ or implement RD-CPM[6].

[1] For more on the effect of ‘float’ see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/PDF/Schedule_Float.pdf

[2] From ISO 21500 Guide to Project Management,

[3] The calculations for these constructs are on Miklos’s blog at: https://www.linkedin.com/in/miklos-hajdu-a1418862

[4] For more on ‘Links, Lags and Ladders’ see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/PDF/Links_Lags_Ladders.pdf

[5] For more on continuous relationships see: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877705815031811

[6] For more on RD-CPM see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1035_RD-CPM.pdf