A string of disasters over the last couple of years suggest many business and government leaders simply do not understand ‘practical ethics’. Through naivety, undue optimism, or laziness, they have set up situations based on blind trust in the ethical standards of others resulting in deaths, injury and the loss of $billions.

A string of disasters over the last couple of years suggest many business and government leaders simply do not understand ‘practical ethics’. Through naivety, undue optimism, or laziness, they have set up situations based on blind trust in the ethical standards of others resulting in deaths, injury and the loss of $billions.

Just a few examples:

- The ‘Home insulation program’ of 2008/9 resulted in 4 deaths, numerous house fires and many well established businesses being destroyed. The naive assumption by the Government seemed to be that with $millions of government funding easily accessed, businesses would still act ethically, train staff and comply with occupational health and welfare standards. The failure by businesses to meet this expectation has resulted in numerous prosecutions after the damage was done.

- The outsourcing of technical and further education training (TAFE) to the private sector. Private providers under the VET Fee-Help scheme are paid for students signed up to courses, not for students qualified from courses – the naive assumption by the Government seemed to be that with $millions of government funding easily accessed, businesses would still act ethically and only sign up students that could benefit from the courses and would deliver good training outcomes. $hundreds of millions of public funds have been wasted – most of which can never be recovered.

- Downer EDI’s Board of Directors appear to have blindly trusted their management to run the disastrous $3 billion Waratah train project. Normal governance feedback seemed to have been ignored to the point where the Directors were unable to get information on the project when needed, blowing a $20 million loss into a $200 million loss.

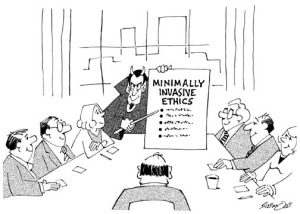

In each of these cases the government and business leaders seemed to have either assumed everyone would act ethically or relied on Adam Smith’s ‘Invisible hand’ (a flawed theory much loved by the rabid right, particularly in the USA). Unfortunately ethics is not that simple! Writing a code of ethics[i] is a relatively simple process; encouraging people to live up to the code is far more difficult. There are several factors needed:

- First, the organisations leaders need to lead by example. The ethical standards of the organisation and its supply chain are unlikely to exceed the standards set by the leadership (see: Ethical Leadership).

- Second, the expected standards need to be clearly and unambiguously articulated. Saying you require one standard of behaviour and then paying people to perform differently will inevitably lead to the organisation getting what it has paid for (see: The normalisation of deviant behaviours).

- Third, the governance and management systems need ‘real-time’ feedback to both encourage the desired standards of behaviour and to detect any ‘slips’ very early in the process so corrective actions can be implemented before there is a major issue (see: Self Correcting Processes).

Unfortunately governments in particular are reasonably good at enforcing standards years after the breach took place and seem to assume that the ‘deterrent effect’ will suffice to maintain ethical standards – this assumption patently does no work! I doubt the £2.25m fine imposed on UK consultancy Sweett Group[ii] for bribing a prominent United Arab Emirates (UAE) businessman in return for work will have much effect on other unethical business people contemplating paying a bribe – for a start, no one expects to get caught. The ‘pink batt’ prosecutions occurred years after the scheme was closed, prosecutions under the VET Fee-Help scheme are still to eventuate (and rip-offs are still continuing). The simple fact is the fear of a potential prosecution in a few years time compared to the opportunity to make $millions now has very little effect on unethical people.

Conversely, over policing ‘ethics’ and watching every move can be as destructive as ‘blind trust’. If people feel they are not trusted, there is no incentive for them to act ethically. Micro management is a major de-motivator and will inevitably lead to suboptimal performance with people doing ‘just enough’ and seeing how much they can get away with[iii]. This approach stifles innovation and creativity.

Practical ethics requires pragmatic trust. You need to trust the people you are working with, governing or managing, but have agreed processes that provide feedback and monitoring, that demonstrates your trust is being honoured.

- In my ‘Six functions of governance’ management control functions are expected to provide feedback to the governing body that allows it to hold its management accountable and ensure conformance by the organisation being governed. Had these functions been implemented effectively EDI-Downer would be in a much better position today.

- Demand feedback – even if you do not want to hear bad news! The recent announcement by CSIRO that its climate division will be virtually eliminated may be a pragmatic response to government initiatives and cost cutting but serves no one in the long term. Governments and business rely on climate science to make billion-dollar decisions. Without it, they will be relying on guesswork. Shooting the messenger simply means everyone is ‘flying blind’.

- Build feedback into management systems. In the various government debacles mentioned above (and others) simple changes in process could have reward desirable outcomes rather than rewarding unethical behaviour. The purpose of any TAFE course is to educate a person and demonstrate learning by success in an exam. Why not pay most of the money on completion of the course? Then make sure audit processes are in place to validate the exam performance is genuine – these exist and are easily applied.

Pragmatic trust is a graduated process – as people demonstrate their trustworthiness and ethical standards less oversight is needed (but less does not mean no oversight); the challenge is to design systems that reward desirable behaviours and outcomes creating a win-win, people who demonstrate high ethical standards are rewarded.

This approach is the antithesis of the current government approach which seems to rely on blind trust, assumes everyone is ethical, and as a consequence directly benefits unethical behaviours (at least in the short term). Not only have the $millions paid out in VET Fees to unethical providers resulted in minimal return to the government; they have actively encouraged unethical standards and have damaged businesses and organisations that do offer quality courses. A lose-lose outcome in which the only winners are the unethical businesses that have ripped off the system – the Pink Batts Royal Commission found a similar effect on the insulation businesses.

Ethics are by definition based on the standards of behaviour considered acceptable by a group[iv]. When a significant proportion of the groups members start to let standards slip, they will tend to drag the rest of the group with them down the slippery slope – it is very hard to stand out against the normally accepted behaviours of your group. And as with any slippery mountain slope, it is far easier to slide towards the bottom than to keep your footing and climb towards the top.

Ethics are by definition based on the standards of behaviour considered acceptable by a group[iv]. When a significant proportion of the groups members start to let standards slip, they will tend to drag the rest of the group with them down the slippery slope – it is very hard to stand out against the normally accepted behaviours of your group. And as with any slippery mountain slope, it is far easier to slide towards the bottom than to keep your footing and climb towards the top.

The role of ethical leaders is first to set the ethical standards, then live up to the standards themselves, and finally require their followers to conform to the standards using pragmatic trust and encouragement rather than after the event punishment.

[i] The PMI Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct is a good example: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/PDF/PMICodeofEthics.pdf

[ii] See: http://www.globalconstructionreview.com/news/sweett-group-must-pay-32m-bri7bery-a7bu-dh7abi/

[iii] For more on motivation see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1048_Motivation.pdf

[iv] For more on ethics and leadership see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1001_Ethics.pdf