Probably the biggest single challenge in stakeholder communication is dealing with risk – I have touched on this subject a few times recently because it is so important at all levels of communication.

Projects are by definition uncertain – you are trying to predict a future outcome and as the failure of economic forecasts and doomsday prophets routinely demonstrate (and bookmakers have always known), making predictions is easy; getting the prediction correct is very difficult.

Most future outcomes will become a definite fact; only one horse wins a race, the activity will only take one precise duration to complete. What is uncertain is what we know about the ‘winner’ or the duration in advance of the event. The future once it happens will be a precise set of historical facts, until that point there is always a degree of uncertainty, and this is where the communication challenge starts to get interesting……

The major anomaly is the way people deal with uncertainty. As Douglas Hubbard points out in his book the Failure of Risk Management: “He saw no fundamental irony in his position: Because he believed he did not have enough data to estimate a range, he had to estimate a point”. If someone asks you what a meal costs in your favourite restaurant, do you answer precisely $83.56 or do you say something like “usually between $70 and $100 depending on what you select”? An alternative answer would be ‘around $85’ but this is less useful than the range answer because your friend still needs to understand how much cash to take for the meal and this requires an appreciation of the range of uncertainties.

In social conversations most people are happy to provide useful information with range estimates and uncertainty included to make the conversation helpful to the person needing to plan their actions. In business the tendency is to expect the precisely wrong single value. Your estimate of $83.56 has a 1 in 3000 chance of actually occurring (assuming a uniform distribution of outcomes in a $30 range). The problem of precisely wrong data is discussed in ‘Is what you heard what I meant?’.

The next problem is in understanding how much you can reasonably expect to know about the future.

- Some future outcomes such as the roll of a ‘true dice’ have a defined range (1 to 6) but previous rolls have absolutely no influence on subsequent rolls, any number can occur on any roll.

- Some future outcomes can be understood better if you invest in appropriate research, the uncertainty cannot be removed, but the ‘range’ can be refined.

This ‘know-ability’ interacts with the type of uncertainty. Some future events (risks) simply will or won’t happen (eg, when you drop your china coffee mug onto the floor it will either break or not break – if it’s broken you bin the rubbish, if it’s not broken you wash the mug and in both situations you clean up the mess). Other uncertainties have a range of potential outcomes and the range may be capable of being influenced if you take appropriate measures.

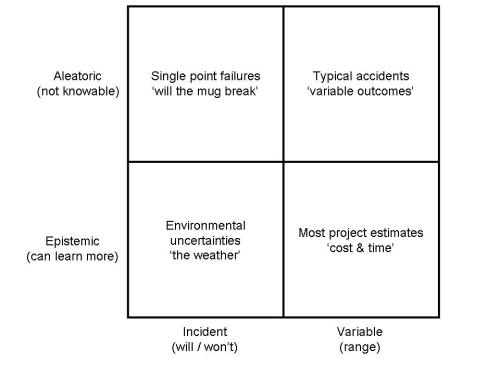

The interaction of these two factors is demonstrated in the chart below, although it is important to recognise there are not absolute values most uncertainties tend towards one option or the other but apart from artificial events such as the roll of a dice, most natural uncertainties occur within the overall continuum.

Putting the two together, to communicate risk effectively to stakeholders (typically clients or senior managers) your first challenge is to allow uncertainty into the discussion – this may require a significant effort if your manager wants the illusion of certainty so he/she can pretend the future is completely controllable and defined. This type of self-delusion is dangerous and it’s you who will be blamed when the illusion unravels so its worth making the effort to open up the discussion around uncertainty.

Then the second challenge is to recognise the type of uncertainty you are dealing with based on the matrix above and focus your efforts to reduce uncertainty on the factors where you can learn more and can have a beneficial effect on future outcomes. The options for managing the four quadrants above are quite different:

- Aleatoric Incidents have to be avoided (ie, don’t drop the mug!)

- Epistemic Incidents need allowances in your planning – you cannot control the weather but you can make appropriate allowances – determining what’s appropriate needs research.

- Aleatoric Variables are best avoided but the cost of avoidance needs to be balanced against the cost of the event, the range of outcomes and your ability to vary the severity. You can avoid a car accident by not driving; most people accept the risk and buy insurance.

- Epistemic Variables are usually the best options for understanding and improvement. Tools such as Monte Carlo analysis can help focus your efforts on the items within the overall project where you can get the best returns on your investments in improvement.

Based on this framework your communication with management can be used to help focus your efforts to reduce uncertainty within the project appropriately. You do not need to waste time studying the breakability of mugs when dropped; you need to focus on avoiding the accident in the first place. Conversely, understanding the interaction of variability and criticality on schedule activities to proactively managing those with the highest risk is likely to be valuable.

Now all you have to do is convince your senior stakeholders that this is a good idea; always assuming you have any after the 21st December!*

____________________

*The current ‘doomsday’ prophecy is based on the Mayan Calendar ending on 21st December 2012 but there may be other reasons for this: