For the last 13 years I’ve been part of the team developing delivering the Project Governance and Controls Symposium in Canberra. In a couple of weeks’ time from the 22nd to 24th August, we will be celebrating the 10th Anniversary symposium at the Canberra Rex Hotel, for more on this see: https://www.pgcsymposium.org.au/

The concept of linking project controls and governance may have been seen as something unusual a decade ago, but as an article in this month’s Australian Institute of Company Directors magazine, the topic is (or should be) of significant interest to both senior managers and directors. In every organization there are a number of projects that are central to the organization’s ability to respond to change, and deliver its strategy. These projects affect the performance of the organization and therefore the performance of the project has legal implications for the organization and its directors and officers. There have been successful prosecutions of numerous organizations that failed to manage project issues effectively.

Director’s responsibilities

Each director has a core responsibility to be involved in the management of the company and to take all reasonable steps to be in a position to guide and monitor management[1]. This requires information, and under the Corporations Act, the director can rely on information provided by the company’s officers and employees, provided the director has reasonable grounds to believe they are reliable and competent people, and the director has made an independent assessment of the information. The legislation also includes a positive due diligence obligation in respect to a number of key business activities including financial reporting, OH&S, and the management of ‘mission-critical risks’.

This means where a project or program has been established to deliver a critical capability the directors need to be across the project and understand its status and predicted outcomes. This of course need information!

Management’s responsibilities

While directors have been subject to legally imposed obligations for decades, management has largely been able to avoid legal liability. This is changing and the legal obligations of company officers and employees who provide information to the board are steadily increasing. The law requires information provided to the board to be complete and accurate.

The Officers of the company will typically include most members of the ‘C-suite’ and may extend to other senior management roles. As an officer, each person is subject to a general statutory duty of care and diligence that applies to all aspects of their role including briefing the board[2].

This was extended in 2019 when the Corporations Act was amended by the Treasury Laws Amendment (Strengthening Corporate and Financial Sector Penalties) Act to create new civil penalties for both corporate officers and employees who mislead the board by providing incorrect information, or by omitting information. This applies to any employee who ‘makes available or gives information, or authorizes or permits the making available or giving of information’ to a director that relates to company affairs. This provision applies to information in any form, all that is required is for the information to be materially misleading, which includes ‘half-truths’. If the information has been provided without the person taking reasonable steps to ensure that the information is not misleading, they have contravened section 1309 (12) of the Act.

The reasonable steps include the person being able to show they made all reasonable enquiries under the circumstances and having done so believed the information was reliable, accurate, and not misleading. If these duties are breached ASIC can run civil penalty proceedings against the individuals concerned without having to show they knew the information was materially misleading or intended to mislead.

What this means for project controls

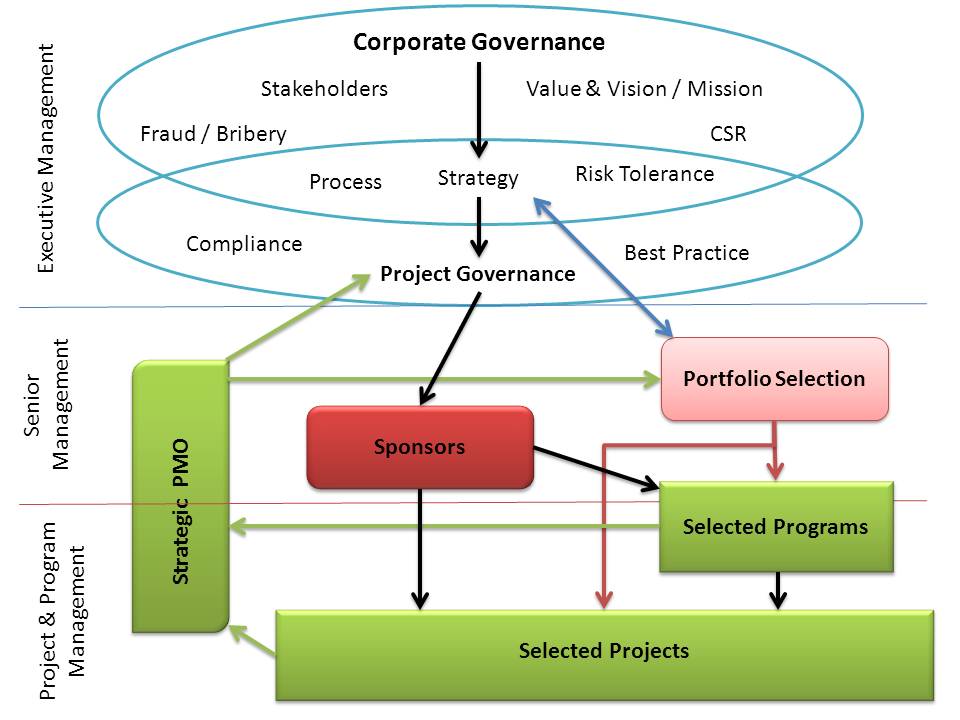

Within an organization where the delivery of the benefits, or capabilities, created by projects is a core part of the organizations business strategy, information on changes in the expected delivery date and/or cost to complete important projects is likely to be seen as information that is material to the affairs of the company with a particular focus on its continuous disclosure obligations. Failure to comply with the Corporations Act has consequences for the company[3]. But where the directors were acting reasonably on the information provided to them, liability may well flow down to the officers and employees who provided inaccurate, or incomplete information to the board.

The solution is simple, set up governance and controls systems that provide ACCURATE information[4].

But achieving this is not easy, success requires the right culture, management support, and capable staff. However, even with these factors in place providing correct information is not easy. One of the major challenges is predicting the likely completion date for both ‘Agile’ and ‘distributed’ projects where traditional CPM simply does not work! And without knowing the overall timeframe, any cost predictions are questionable. Using EVM and ES is of course one solution that’s ideal for larger projects; a simpler, more pragmatic option for most normal projects is to use WPM to calculate the current status and projected end date. For more on WPM see: https://mosaicprojects.com.au/PMKI-SCH-041.php#WPM

This is just a brief overview, there are two ways to find out more:

- Attend PGCS on the 22nd to 23rd August, in-person or virtually: https://www.pgcsymposium.org.au/

- Make use of the free information on Governing the organization’s Projects, Programs and Portfolios at: https://mosaicprojects.com.au/PMKI-ORG-005.php#Process3

[1] See the ‘Centro case’: ASIC -v- Healey [2011] FCA 717.

[2] In ASIC -v- Lindberg [2012] VSC 322, the former CEO of the Australian Wheat Board admitted to failing to inform the board of key issues.

[3] In 2006 Veterinary pharmaceuticals company Chemeq Ltd paid a $500,000 fine, in part for failing to keep the market informed of cost overruns and delays on a project to construct its manufacturing facility [Re Chemeq [2006] FCA 936].

[4] For a definition of ACCURATE Information see: https://mosaicprojects.com.au/Mag_Articles/SA1055_ACCURATE_Information.pdf