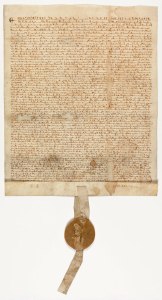

On the 15th June 1215 the Magna Carta (Latin for “the Great Charter”), was sealed by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor. Drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury to make peace between the unpopular King and a group of rebel barons, it promised the protection of church rights, protection for the barons from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, and limitations on feudal payments to the Crown, to be implemented through a council of 25 barons.

Unfortunately, neither side stood behind their commitments, leading to civil war with the rebel barons receiving active support from France. After John’s death, the regency government of his young son, Henry III, reissued the document in 1216, stripped of some of its more radical content, and at the end of the civil war in 1217 it formed part of the peace treaty agreed at Lambeth, where the document acquired the name Magna Carta.

Short of funds, Henry reissued the charter again in 1225 in exchange for a grant of new taxes; and his son, Edward I, repeated the exercise in 1297, this time confirming it as part of England’s statute law. But as important as this document is in English history, it was not ‘unique’ – the Magna Carta is based on a long Anglo-Saxon tradition of governance.

The 1215 Magna Carter was based on The Charter of Liberties, proclaimed by Henry I a century earlier. Henry I was King of England from 1100 to 1135; he was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and came to the throne on the death of his bother in a hunting accident. The Charter of Liberties issued upon his accession to the throne in 1100, and was designed to counteract many of the excesses of his bother William II and shore up support for Henry. Among other things the Charter of Liberties restored the law of Edward the Confessor one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England.

Anglo-Saxon law itself has a long history; the Textus Roffensis currently held in the archives at Rochester, Kent, documents Anglo-Saxon laws from the 7th Century. These laws and practices suggest the rights of individuals were fairly well protected and the King was responsible for governing within the law (see: Arbitration has a long history).

The Norman Conquest of 1066 brought a more imperial style of governing that flowed from the Roman Emperors (post Julius Cesar), based on ‘the divine right of kings’ and a feudal system that placed the King at the top of a hierarchy of power based on the control of land – the King owned all of the land and granted it to Barons in return for allegiance and taxes. The only limitation on the King’s power was the willingness of his barons to accept the King’s rule and if they did not, rebellion was their only option. This type of ‘absolute’ power was wound back a little by the Magna Carta which guaranteed the rights of Nobles and the Church but did little for ordinary people.

However, during the course of its repeated ‘re-issuing’ the Magna Carta did pave the way for Parliamentary government and stood as a powerful counter to attempts by monarchs to assert the divine right of Kings as late at the 17th Century. By the end of the 17th century, England’s constitution was seen as a social contract, based on documents such as Magna Carta, the Petition of Right, and the Bill of Rights. These concepts were taken to the Americas by the early colonists and formed part of the underpinnings of the USA constitution.

The governance message from the Mana Carta is the need for the ‘governor’ to respect the rights of the people being governed. The closer a governor gets to absolute power the greater the tendency to despotism and corruption. Effective governance systems balance the needs and rights of the governor and the governed, operate within an open framework, incorporate checks and balances, and adapt to changing circumstances. ‘Absolute systems’ are almost incapable of changing progressively, the usual course is the governors apply more and more coercion to stay ‘in power’ until eventually the whole system is destroyed by revolution or catastrophe; damaging everyone.

Following Magna Carta, the English constitution evolved and adapted to change and certainly since the restoration of the Monarchy after the English Civil War and Commonwealth of Oliver Cromwell has been designed to adapt and change. Corporate and organisational governance has followed a similar trend and evolved from its inception in the early 17th century into its modern form (see: The origins of governance).

However, whilst the concept of governance has been evolving and the purpose of good governance is to balance the needs and expectations of all stakeholders to the common good, governance failures remain commonplace. Our last blog post Governance and stakeholders highlighted three recent governance failures; the discussion on FIFA in particular highlighting the danger of concentrating nearly absolute power in the hands of one person.

There are some interesting parallels, eight hundred years ago on the banks of the Thames an embattled King John met the English barons who had backed his failed war against the French and were seeking to limit his powers. The sealing of the Magna Carta, symbolically at least, established a new relationship between the king and his subjects. Eight days ago, Sepp Blatter met his advisors near the banks of Lake Genève and sealed his fate by announcing his resignation from FIFA. If FIFA survives, it is highly likely the powers of his successor will be similarly limited by a new ‘charter’.

The bigger question though, is how can these excesses be avoided in future? History tells us that transparency and good information is one of the keys to avoiding excess, as is making the ‘governors’ accountable to the governed. Another is the affected stakeholders being willing to assert their rights before a situation gets out of hand and more desperate measures become necessary.

On two separate occasions I’ve been lucky enough to see one of the four remaining copies of the original Magna Carter, once at Lincoln in the UK, and once as part of an exhibition in Canberra. As we reflect on this document and its 800 year history its worth considering its key message, that good governance requires both limits on power and for the governors to consider the interests of their stakeholders; if these two elements are present, the likelihood of governance failure is going to be significantly reduced. This is equally true for national governments, organisational governance and the governing of projects, programs and portfolios.

Certainly, as far as the governing of projects, programs and portfolios is concerned, both the EVA18 Project Controls Conference in England and our local Project Governance and Controls Symposium are organised by people who believe one of the keys to good governance is having open, effective and robust reporting system in place that deliver accurate information to all relevant stakeholders. The challenge we face is persuading more organisations to invest in this key underpinning of good governance – hopefully we won’t have to wait another 800 years…