A number of current news items have highlighted the complexity and interconnectedness of governance in organisations. The blog post is going to draw together four elements – high pressure projects, bullying, the need for organisations to provide a safe workplace and the need to support people with mental illness; all of which have interconnected governance implications.

To lay the foundation for this post, the interconnected nature of governance has been discussed in our post Governance -v- Management: A Functional Perspective and is best displayed in this ‘petal diagram’

The catalyst for this post are some recent changes in Australian workplace legislation that is forcing all types of organisations to consider how they manage the mental health of their paid and volunteer workforce. In essence these codified requirements are no different to the pre-existing requirements to protect the physical wellbeing of the workforce and others interacting with the organisation, the only difference is mental heath and wellbeing are now overtly covered.

The new uniform national workplace health and safety laws require employers to ensure that workplaces are physically and mentally safe and healthy, and the work environment does not cause mental ill-health or aggravate existing conditions. Under these harmonised laws ‘reckless conduct’ offences incur penalties of up to $3 million for corporations and $600,000 and/or 5 years jail for individuals.

These challenges cannot be avoided; it remains illegal to discriminate against individuals on the grounds of disability, including mental disability, in the same way it is illegal to discriminate on the grounds of age, sex, race, and religious and other beliefs.

These are not trivial issues as the $230,000 penalty (fines and costs) awarded by the Victorian Supreme Court against the former operator of a commercial laundry for ‘workplace abuse’ and the reputations damage suffered by CSIRO (Australia’s premier scientific research organisation), over on-going bullying allegations demonstrate.

There is a growing awareness of psychological hazards in the workplace including bullying, harassment and fatigue; and the consequences of organisational failures in this area can extend well beyond the strict legal liabilities. To avoid prosecution and reputational damage, organisations are increasingly being required to take proactive, preventative actions and implement a culture, reinforced by effectively implemented policies to manage these aspects of workplace health and safety. Attitudes are slow to change and creating a culture that properly respects and protects mental wellbeing will require a sustained focus at the governance levels of the organisation as well as in the day-to-day management of the work place.

The payback for good governance and effective management in this area is that organisations that promote good mental health in the workplace are seen as great places to work, and have higher levels of productivity, performance, creativity, and staff retention, and tend to financially outperform other less well governed organisations. These are very similar findings to organisations that actively support and embrace ‘Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) – apparently the good guys finish first (not last)!!

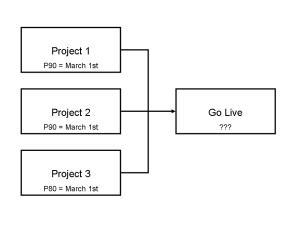

However, managing this change is not going to be simple! Organisations are under ever increasing pressure to adapt to a rapidly changing environment and to produce ‘more with less’ to survive. One of the key capabilities enabling quick and effective strategic change is the domain of project and program management. In response to these organisational pressures, project managers are increasingly being placed under stress to be faster, cheaper and better and to deliver the new capability or ‘thing’ in record time. Couple this to the mistaken belief of some managers that setting ‘stretch targets’ is a way to motivate workers (even though sustained failure is known to be a major cause of stress and demotivation) and you end up with a classic governance dilemma.

Deciding how to best balance these competing demands require an overarching governance policy supported by a sympathetic implementation by management to achieve both a safe work environment and an effective management outcome. In the absence of effective governance managers are left to sort out their own priorities and frequently are driven by short term KPIs focused on easy to measure cost and time performance criteria. In these circumstances concern for performance frequently outweighs concern for people.

These issues are compounded by the fact that far too many middle and project managers lack effective people skills and can easily drift from pushing for performance to micro management to outright bullying. The mental wellbeing risks include applying undue pressure to perform that induces stress leading to depression; as well as more overt acts of aggression and bullying. The Australian Fair Work Amendment Bill of 2013 defines workplace bullying as ‘repeated, unreasonable behaviour directed towards a worker or group of workers that creates a risk to health or safety’.

Unfortunately, at least in the Australian context, bullying is a major unreported problem. A recent survey by the University of Sydney (see the report summary) has found that workplace bullying tends to be peer-to-peer and occurs at all levels of organisations. Most incidents occur within the presence of one’s peers, including bullying in meetings and other managers are unlikely to intervene. The problem is insidious, nearly 50% of the survey respondents reported bullying in the last year, and only 16% organisation assisted the situation when the problem was reported. But, ignoring the issue is a high risk strategy.

All types of organisation need to develop focused strategies to reduce the opportunities for bullying to occur at every level from the board room table down to the shop floor; and to policies backed by procedures to deal with bullying effectively when it does occur, in ways that support the victims. Bullying is illegal, causing damage to a person’s mental health is illegal (and bullying is only one way this can occur) and failing to effectively manage the consequences of mental illness is illegal.

The ongoing damage being caused to CSIRO’s reputation by the publication of the report into bullying within the organisation demonstrates the way these problems can escalate into a major issue for the Board. The on-going publicity associated with potential litigation and prosecutions has a long way to run before the final wash up allows CSIRO to move forward with a clean slate. And, as the CSIRO report suggests, the consequences of breaking the law are likely to be a small part of the overall damage caused governance failures in this important area.

The reason this is primarily a governance issue is the challenge associated with developing a philosophy and culture that empowers management to resolve the dilemma associated with balancing commercial objectives against personal wellbeing objectives – there is no ‘right answer’. It is all too easy for executives to decide the organisation needs a new capability, managers being tasked to deliver the required outcome with inadequate resources, and the project manager to be given an unreasonably short timeframe for delivery. The pressure to ‘perform’ inevitably leading to increases in stress, conflict and potentially bulling. But whilst there are many questions, and decisions, there are few clear answers:

- When does the need to perform and work extended hours slip into workplace fatigue and an unsafe work environment?

- When does the project manager’s desire to push team members for maximum performance slip into bullying?

- Who is responsible for creating the unsafe work environment:

– The PM operating at the tactical level?

– The managers that set the strategic objectives?

– The executives who created the overall environment?

– The ‘governors’ who failed to offer appropriate leadership?

Good management can certainly alleviate some of the symptoms, but good governance is needed to eliminate the root cause and promote mental wellbeing in the workplace. At least in Australia there are now effective laws to help and the data shows improving this aspect of an organisation is good for business, and of course excellent stakeholder management.

The Risk Management Handbook edited by Dr. David Hillson (the ‘risk doctor’) is a practical guide to managing the multiple dimensions of risk in modern projects and business. We contributed Chapter 10: Stakeholder risk management.

The Risk Management Handbook edited by Dr. David Hillson (the ‘risk doctor’) is a practical guide to managing the multiple dimensions of risk in modern projects and business. We contributed Chapter 10: Stakeholder risk management.

I would suggest discussing what you don’t know about the consequences of climate change on your organisation is a serious conversation that needs to be started within your team and your wider stakeholder community.

I would suggest discussing what you don’t know about the consequences of climate change on your organisation is a serious conversation that needs to be started within your team and your wider stakeholder community.