Ed Freeman, one of the people whose work had a significant influence on the development of the Stakeholder Circle® will be speaking in Melbourne tomorrow at an ACCSR event hosted by Deakin University, an event I am really looking forward to attending!

Ed Freeman, one of the people whose work had a significant influence on the development of the Stakeholder Circle® will be speaking in Melbourne tomorrow at an ACCSR event hosted by Deakin University, an event I am really looking forward to attending!

R. Edward Freeman is described as the ‘father’ of Stakeholder theory. In his 1994 book Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, Freeman identifies and models the groups which are the stakeholders of a corporation, and recommends methods by which management can give due regard to the interests of those groups. In short, Stakeholder theory addresses the key question of who really matters and the morals and values associated with managing an organisation.

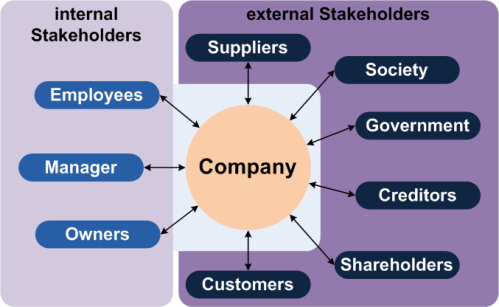

The traditional view of the firm is the shareholder view. This theory states that the shareholders are the owners of the company, and the firm has a binding fiduciary duty to put their needs first, to increase value for them. Stakeholder theory argues that there are other parties involved, including employees, customers, suppliers, financiers, communities, governmental bodies, political groups, trade associations, and trade unions. Even competitors are sometimes counted as stakeholders – their status being derived from their capacity to affect the firm and its other stakeholders.

This wider view is central to the definition of ‘stakeholder’ included in the PMBOK® Guide and the Stakeholder Circle® methodology. The PMBOK® Guide’s definition of stakeholders is: ‘Individuals, groups or organisations who may affect, or be affected by a decision, activity or outcome of a project or perceive this to be the case’.

Whilst this definition would seem sensible, the nature of what is a stakeholder is highly contested with hundreds of definitions existing in the academic literature. Probably the most widely accepted ‘contrary view’ is built on Mitchell’s[1] theory of stakeholder salience. This theory derives a typology of stakeholders based on the attributes of power (the extent a party has means to impose its will in a relationship), legitimacy (socially accepted and expected structures or behaviours), and urgency (time sensitivity or criticality of the stakeholder’s claims).

Legitimacy and the traditional view that stakeholders are ‘the owners’ of an organisation are closely aligned. The implication is that some stakeholders can be ignored because they do not have a ‘legitimate right’ to be considered. I disagree with this view and support Freeman’s wider concept. As he point out in some of his on-line talks:

- Do you want employees that are not committed to the success of the organisation?

- Do you want customers who do not value your offerings?

- Can you afford to alienate the society in which you operate?

Add to Freeman’s questions the fact that ‘non-legitimate’ stakeholders can still create major problems for an organisation through social media and other channels makes taking a wider view of stakeholders seem inevitable. Ultimately the success of an organisation depends on finding ways to align and fulfil the needs of all of its stakeholders – those that do this best are most successful.

The paradox is that investing in successful stakeholder engagement ultimately benefits the organisation’s owners. Numerous surveys have demonstrated that corporations that actively embrace ‘corporate social responsibility’ consistently out perform those that focus on profits first. To quote Freeman: “Every business creates, and sometimes destroys, value for customers, suppliers, employees, communities and financiers. The idea that business is about maximizing profits for shareholders is outdated and doesn’t work very well, as the recent global financial crisis has taught us. The 21st Century is one of ‘Managing for Stakeholders’. The task of executives is to create as much value as possible for stakeholders without resorting to tradeoffs. Great companies endure because they manage to get stakeholder interests aligned.”

The problem with adopting the wider definition of stakeholders implicit in stakeholder theory is managing the large number of potential stakeholders it embraces. Some will be supportive, others neutral or antagonistic; some will be more important than others. Determining who is important at this point in time (and what to do about them) requires a pragmatic methodology focused on:

- Identifying, understanding and prioritising the current stakeholder community.

- Determining a communication plan to affect desired changes in the attitude of important stakeholders and to maintain or enhance the attitude of the general stakeholder community (usually segmented).

- Implementing the communication plan.

- Regular reviews to assess the effectiveness of the communication process, update the stakeholder community, and refocus your stakeholder engagement efforts.

Dealing with the amount of data needed to implement these processes requires a rigorous methodology supported by robust tools! The Stakeholder Circle® has been designed for this purpose, the methodology is freely available.

[1]Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts, 1997 Mitchell, Agle, and Wood.

Hi Lynda, what an interesting article thank you for posting it.

Pingback: Modèle de supervision du management | Lignes de défense des parties prenantes | Gouvernance | Jacques Grisé

Pingback: The normalisation of deviant behaviours | Stakeholder Management's Blog

Pingback: The normalisation of deviant behaviours | Mosaicproject's Blog

Pingback: How to Get Your Team to Embrace Change