The world loves 2×2 matrices – they help make complex issues appear simple. Unfortunately though, some complex issues are complex and need far more information to support effective decision making and action. The apparent elegance of a 2×2 view or the world quickly moves from simple to simplistic.

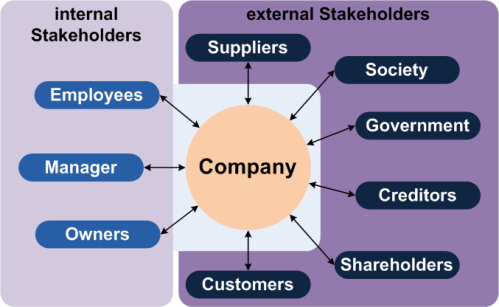

One such situation is managing project and program stakeholders and convincing the stakeholders affected by the resulting organisational change that change is necessary and potentially beneficial. As a starting point, some stakeholders will be unique to either the project, the overarching program or the organisational change; others will be stakeholders in all three aspects, and their attitude towards one will be influenced by their experiences in another (or what others in their network tell them about ‘the other’).

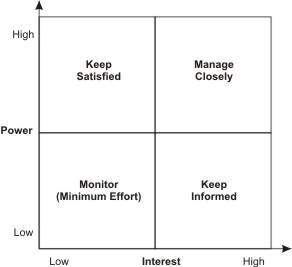

The problem with a simple 2×2 view of this complex world is the assumption that everyone falls neatly into one of the four options and everyone categorised as belonging in a quadrant can be managed the same way. A typical example is:

Power tends to be one dimension, and can usually be assessed effectively, the second dimension can include Interest, Influence, or Impact none of which are particularly easy to classify. A third dimension can be included for very small numbers of stakeholders by colouring the ‘dots’ typically to show either importance or attitude.

The problem is you may have a stakeholder assessed as high power, low interest who opposes your work, who you need to be actively engaged and supportive – ‘keep satisfied’ is a completely inappropriate management strategy.

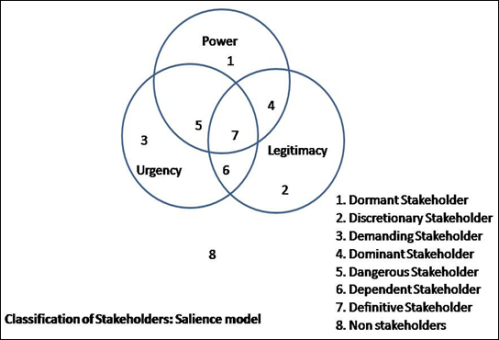

The Salience Model developed by Mitchell, Agle, and Wood. (1997) introduces the concepts of urgency and legitimacy.

Urgency refers to the degree of effort the stakeholder is expected to expend in creating or defending its ‘stake’ in the project, this is an important concept! However the concepts of ‘legitimate stakeholders’ and non-stakeholders are inconsistent with stakeholder theory[1] and PMI’s definition of a stakeholder – anyone who believes your project will affect their interests can make themselves a stakeholder (even if their perception is incorrect) and will need managing. This model also ignores the key dimension of supportive / antagonistic.

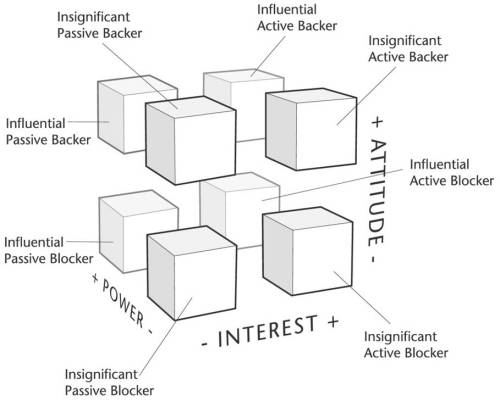

The three dimensional Stakeholder Cube is a more sophisticated development of the simple 2×2 chart. The methodology supports the mapping of stakeholders’:

- Interest (active or passive);

- Power (influential or insignificant); and

- Attitude (backer or blocker).

This approach facilitates the development of eight typologies with suggestions on the optimum approach to managing each class of stakeholder (Murray-Webster and Simon, 2008[2]). However, the nature of the chart makes it difficult to draw specific stakeholders in the grid, or show any relationships between stakeholders and the activity. However, as with any of the other approached discussed so far, the classifications can be used to categorise the stakeholders in a spreadsheet or database and most of the key dimensions needed for effective management are present in this model. The two missing elements are any form of prioritisation (to focus effort where it is most needed) and the key question ‘Is the stakeholder in the right place?’ is not answered.

Information needed for a full assessment

The factors needed for effective stakeholder management fall into two general categories, firstly the information you need to prioritise your stakeholder engagement actions; second the information you need to plan your prioritised engagement activities.

The two basic elements needed to identify the important stakeholders at ‘this point in time’ are:

- Firstly the power the stakeholder has to affect the work of the project. This aspect tends to remain stable over time)

- Secondly the degree of ‘urgency’ associated with the stakeholder – how intense are the actions of the stakeholder to protect of support its stake? This aspect can change quickly depending on the interactions that have occurred between the project team and the stakeholder.

I include a third element in the Stakeholder Circle® methodology[3], how close is the stakeholder to the work of the project (proximity) – stakeholders actively engaged in the work (eg, team members) tend to be need more management attention than those relatively remote from the work.

The next step is to assess the attitude of the important stakeholders towards the work of the project. Two assessments are needed, firstly what is the stakeholder’s current attitude towards the project and secondly what is a realistically desirable attitude to expect of the stakeholder that will optimise the chance of project success?

Attitudes can range from actively supportive of the work through to active opposition to the work. The stakeholder may also be willing to engage in communication with you or refuse to communicate[4]. If you need to change the stakeholder’s attitude, you need to be able to communicate!

From this information you can start to plan your communication. Important stakeholders whose attitude is less supportive than needed require carefully directed communication. Others may simply require routine engagement or simple reporting[5].

If this all sounds like hard work it is! But it’s far less work then struggling to revive a failed project. This theme is central to my new book, Making Projects Work, Effective stakeholder and communication management[6]. You generally only get one chance to create a first impression with your stakeholders – it helps to make it a good one.

[1] For more on ‘stakeholder theory’ see:

/2014/07/11/understanding-stakeholder-theory/

[2] For more information see www.lucidusconsulting.com

[3] For more on stakeholder prioritisation see: http://www.stakeholder-management.com/shopcontent.asp?type=help-4

[4] For more on assessing stakeholder attitudes see: http://www.stakeholder-management.com/shopcontent.asp?type=help-6

[5] For more on the ‘three types of stakeholder communication’ see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/Mag_Articles/SA1020_Three_types_stakeholder_communication.pdf

[6] For more on the book see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/Book_Sales.html#MPW