This post offers a detailed look at the new PMP examination content and what you can expect to see different in a exam taken after the 2nd November 2015.

This post offers a detailed look at the new PMP examination content and what you can expect to see different in a exam taken after the 2nd November 2015.

Notes:

- PMI have moved the start date back from the originally publicised date in November to January 2016.

- There will be no changes to the CAPM exam or any other PMI credential other than the PMI-ACP.

- Our free daily PMP questions are now aligned to the new exam see: http://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/Training-PMP-Q-Today.html

- All PMP of our courses starting from September 1st will be aligned to the new PMP examination, see: http://www.mosaicproject.com.au/

The starting point for this update is the PMP Role Delineation Study (RDS) completed in April 2015, which has provided an updated description of the role of a project management professional and will serve as the foundation for the updated PMP exam. To ensure its validity and relevance, the RDS update has captured input from project management practitioners from all industries work settings, and regions. The research undertaken to update the RDS included focus groups, expert input and a large-scale, global, survey of Project Management Professional (PMP)® certification holders.

Overview of Changes

The RDS defines the domains and tasks a project manager will perform plus the skills and knowledge that a competent project manager will have. The five ‘domains’ of Initiating, Planning Executing, Mentoring & Controlling and Closing remain unchanged, although there has been a slight reduction in the importance of ‘closing’ and an increased emphasis on executing (reflected in the allocation of questions). The other major changes are:

- An emphasis on business strategy and benefits realisation: this new, included because many PMs are being pulled into a project much earlier in its life when business benefits are identified. There is also an increased focus across all of the other domains on delivering benefits (not just creating deliverables).

See more on benefits management. - The value of lessons learned now has added emphasis: lessons should be documents across the whole project lifecycle and the knowledge gained transferred to the ‘organisation’ and the project team. See more on Lessons Learned.

- Responsibility for the project charter shifted to the Sponsor: Most project managers are not responsible for creating the charter; the Sponsor or project owner is primarily responsible. The PM is a contributor to the development and is responsible for communicating information about the project charter to the team and other stakeholders once the project starts.

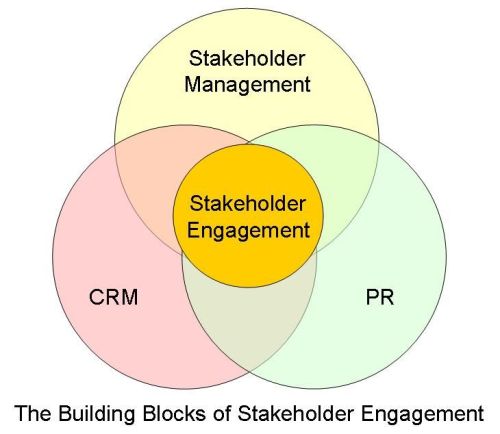

See more on the Project Charter. - Added emphasis on enhancing project stakeholder relationships and engagement: The RDS sees stakeholder engagement as a two way relationship rather than a one-way reporting function. Communication is expanded include an emphasis on relating and engaging with stakeholders. This is the theme of our last post, see: The Elements of Stakeholder Engagement.

Major Content Changes

A summary of the major content changes is:

Domain 1 Initiating the Project

Percentage of questions unchanged 13% = 26 questions.

Three tasks added:

– Task 2: Identify key deliverables based on business requirements.

– Task 7: Conduct benefits analysis.

– Task 8: Inform stakeholders of approved project charter.

One task deleted:

– Old Task 2: Define high level scope of the project.

One task significantly changed:

– Task 5: changed from ‘develop project charter’ to ‘participate in the development of the project charter’.

Major changes in the knowledge and skills required for this domain.

Domain 2 Planning the Project

Percentage of questions unchanged 24% = 48 questions.

One task added:

– Task 13: Develop the stakeholder management plan.

One task significantly changed:

– Task 2: expanded from ‘create WBS’ to ‘develop a scope management plan (including a WBS if needed)’.

The knowledge and skills required for this domain have been revised but basically cover the same capabilities.

Domain 3 Executing the Project

Percentage of questions increased from 30% to 31% = 62 questions.

Two tasks added:

– Task 6: Manage the flow of information to stakeholders.

– Task 7: Maintain stakeholder relationships.

One task deleted:

– Old Task 6: Maximise team performance.

The knowledge and skills required for this domain have been revised but basically cover the same capabilities with the exception of the addition of ‘Vendor management techniques’.

Domain 4 Monitoring and controlling the project

Percentage of questions unchanged 25% = 50 questions.

Two tasks added:

– Task 6: Capture, analyse and manage lessons learned.

– Task 7: Monitor procurement activities.

One task deleted:

– Old Task 6: Communicate project status to stakeholders.

The knowledge and skills required for this domain have been revised and expanded.

Domain 5 Closing the project

Percentage of questions reduced from 8% to 7% = 14 questions

No new tasks added or significantly changed.

The knowledge and skills required for this domain have been revised but basically cover the same capabilities.

Cross Cutting Knowledge and Skills

Cross cutting knowledge and skills are capabilities required by a project manager in all of the domains. This areas of the RDS has been increased significantly. The full list of knowledge and skills is

(* = included in previous RDS):

1. Active Listening*

2. Applicable laws and regulations

3. Benefits realization

4. Brainstorming techniques*

5. Business acumen

6. Change management techniques

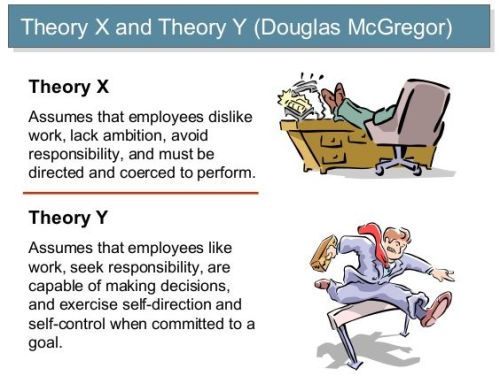

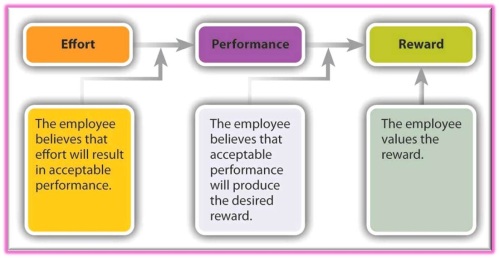

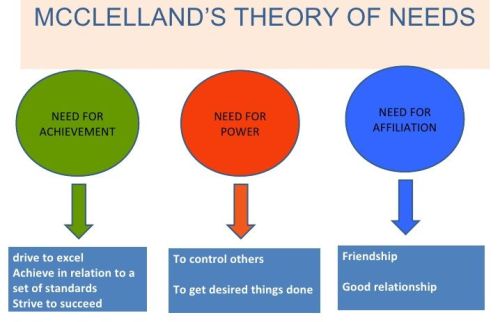

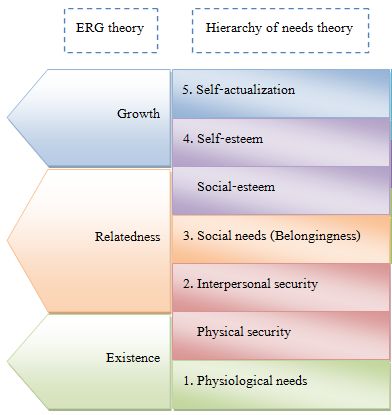

7. Coaching, mentoring, training, and motivational techniques

8. Communication channels, tools, techniques, and methods*

9. Configuration management

10. Conflict resolution*

11. Customer satisfaction metrics

12. Data gathering techniques*

13. Decision making*

14. Delegation techniques

15. Diversity and cultural sensitivity*

16. Emotional intelligence

17. Expert judgment technique

18. Facilitation*

19. Generational sensitivity and diversity

20. Information management tools, techniques, and methods*

21. Interpersonal skills

22. Knowledge management

23. Leadership tools, techniques, and skills*

24. Lessons learned management techniques

25. Meeting management techniques

26. Negotiating and influencing techniques and skills*

27. Organizational and operational awareness

28. Peer-review processes

29. Presentation tools and techniques*

30. Prioritization/time management*

31. Problem-solving tools and techniques*

32. Project finance principles

33. Quality assurance and control techniques

34. Relationship management*

35. Risk assessment techniques

36. Situational awareness

37. Stakeholder management techniques*

38. Team-building techniques*

39. Virtual/remote team management

Two skills that have been dropped are knowledge of:

– PMI’s Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct

(although this continues to have a major influence on the approach PMI

expects project managers to adopt in the exam and the ‘real world’).

– Project Management Software

The effect on the exam

PMI have advised that 25% of exam content will be new, focused on new topic areas (ie, the eight new tasks) added to examination, in addition, many other questions will be updated to reflect changes in the descriptions of tasks and changes in the underpinning skills and knowledge requirements. We will be updating our materials from September 2015 to take these changes into account. Fortunately a large percentage of the ‘new’ materials from the RDS are already part of our PMP course (because we felt they were essentially good practice) or in other training courses we offer – overall this update makes very good sense.

Many aspects of the PMP exam are not changing including the eligibility requirements, formal training requirements, the passing score (which remains secret) and the design of the questions, many of which are scenario based seeking information on what should you do.

There is no change to other PMI exams, the CAPM, PMI-SP and other credentials remain unaltered.

Will there be more changes?

The sort answer if ‘yes’! Changes in the RDS occur every 3 to 5 years and as a consequence, the exam content outline changes, new topics are added, and shift in weighting occur.

In addition, the PMP exam also changes when the PMBOK® Guide is update (this is due in 2017). Changes in the PMBOK® Guide cause changes in terminology, changes to elements of process groups and exam questions are changed to reflect these alterations. However, many other references are used to create PMP content in addition to the PMBOK, and if the PMBOK has contents not reflected in the RDS this section not examined.

So moving forward, the current version of the exam is active until 1st Nov. 2015; the new version of the exam is available from 2nd Nov. 2015, and the next change will be in mid-to-late 2017.

For this change, there is no change over period (including for re-sits) – the ‘old’ exam applies up until the 1st, the new exam from the 2nd November. Both before and after the change, your exam results available immediately if you take a computer based test. For more on the current examination, fees, eligibility requirement, etc, see: http://www.mosaicproject.com.au/pmp-training-melbourne/.

A different set of changes has been announced for the PMI-ACP (Agile) credential (visit the PMI website for more details).

PMI have also announced changes to the way PDUs are earned as part of their Continuing Certification Requirement (CCR) program, effective from the 1st December 2015. For more on this change see: /2015/06/06/pmi-pdu-update/

It’s a New Year and by now most of us will have failed to keep our first set of New Year resolutions! But it’s not too late to re-focus on doing our projects better (particularly in my part of the world where summer holidays are coming to an end and business life is starting to pick up). Nothing in the list below is new or revolutionary; they are just good practices that help make projects successful.

It’s a New Year and by now most of us will have failed to keep our first set of New Year resolutions! But it’s not too late to re-focus on doing our projects better (particularly in my part of the world where summer holidays are coming to an end and business life is starting to pick up). Nothing in the list below is new or revolutionary; they are just good practices that help make projects successful. Almost all of the items listed require action by people other than the project manager – this highlights the fact that projects are done by people for people and the key skill required by every project manager is the ability to influence, motivate and lead stakeholders both in the project team and in the wider stakeholder community.

Almost all of the items listed require action by people other than the project manager – this highlights the fact that projects are done by people for people and the key skill required by every project manager is the ability to influence, motivate and lead stakeholders both in the project team and in the wider stakeholder community.