When it comes to effective communication, a clear, concise and easily defined name for something is essential if you want people who are not directly involved in your special disciple to understand your message. Jargon and ambiguity destroy understanding and damage credibility.

Potentially one of the major reasons senior executives still fail to understand ‘project management’ within their organisations is the fact that the project management profession uses its special terms in a multitude of different ways……

There are four generally recognised focuses within the overall domain of ‘project management’ Portfolio management, Program management, Project management and the overarching capabilities needed by an organisation to use project, program and portfolio (PPP) management effectively.

The starting problem is implicit in the above paragraph, ‘project management’ can be used as a ‘collective noun’ and mean all four areas of management or specifically to mean the management of a project.

The next problem is if project management means the management of a project, exactly what is a project? The current definitions for a project are very imprecise and can apply to virtually anything. A more precise definition is discussed in Project Fact or Fiction.

Program management is fairly consistently defined in the literature and involves both the management of multiple projects and the realisation of benefits for the organisation. There are still legacy problems though; the ‘Manhattan Project’ to create the first atomic bombs during WW2 was a massive program of work involving dozens of separate projects.

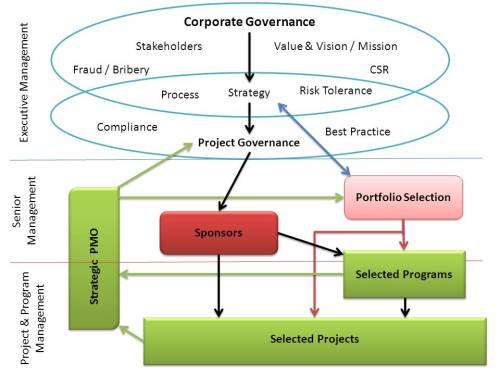

Similarly, Portfolio management is fairly consistently defined. The core element of portfolio management is deciding on the best investment strategy for the organisation to meet its strategic objective through investing in new selected projects and programs and reviewing current ‘investments’ to ensure the project or program is continuing to deliver value (and closing those that are not to redirect the resources to a better ‘investment option’.

Both Program management and Portfolio management are relatively new concepts and have the advantage of being developed at a time where wide reaching communication was relatively easy allowing a consistency of though and definition. Where the real problems emerge is in the realm of the overall organisational capabilities to use PPP concepts effectively.

The management space around the core PPP management functions includes:

- Governance

- Multi-Project management

- Organisational enablers such as PMOs, etc

- The ‘management of projects’ (Prof. Peter Morris)

- Benefits realisation

- Organisational change management

- Value creation

In general terms this area of management responsibilities can be picked up if ‘project management’ is used as an overarching term. Some times, some aspects get absorbed into people’s definition of portfolio management and program management. But this ‘absorption’ does not really help develop clarity; for example, whilst benefits realisation is generally seen as part of program management, this does not help deal with the realisation of benefits for the 1000s of project that are not part of a program, etc.

Apart from project, program and portfolio management as defined I believe the global project management community, including academia and the major associations need to make a focused effort to develop a ‘standard’ naming convention for these various aspects of ‘project management’ – if we cannot be consistent in our use of terms our stakeholders will be permanently confused and confused stakeholders are unlikely to be supportive!

I feel there are three distinct aspects to this ‘fuzzy space’:

- The first is governance. The role and function of governance in the PPP domain was outlined in Patrick Weaver’s recent presentation to the Project Governance and Controls Symposium in Canberra: Stepping up to Governance – the development of ISO 21503.

- The second is the ability of an organisation to effectively select and support its project, program and portfolio management efforts. This includes the ‘management of projects’, organisation enablers and multi-project management: The Strategic Management of Projects.

- The third area is the link between PPP, operations, strategy and value, encompassing benefits realisation, value creation and integration with organisational change management (which is an already established management discipline). I don’t have a good name for this critical area of our professions contribution to organisations but it is probably the most important from the perspective of executive management.

The overall architecture of the discipline of PPP management looks something like this:

The challenge is to start moving towards a consensus on a naming convention for these aspects of ‘project management’ so we can start communicating clearly and concisely with all of our stakeholders. Hopefully this post will start some discussions.