The opening day of the Project Zone Congress included a full day track focused on Project Portfolio Management. The quality of the presentations made it one of the most interesting day’s I’ve spent in a very long time!

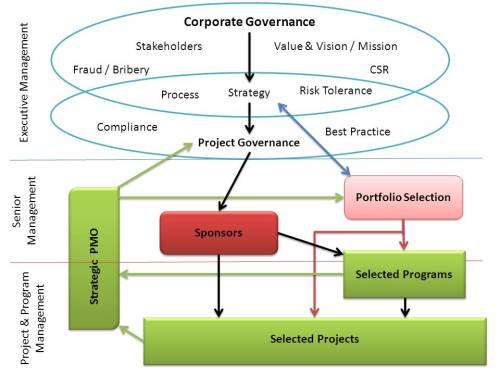

The presentations linked the critical importance of a strategic PMO to effective portfolio management and PPP governance. The importance of ‘doing the right projects’ was highlighted by a presentation from SAP; 20% of the world’s business involves one organisation delivering a ‘project’ to another organisation, and then there is the increasing tendency for organisations to achieve growth and change by commissioning internal project.

The first key message from the day was the vital importance of each organisation developing a realistic and achievable ‘strategic road map’, with specific milestones, that define how the organisations strategy will be achieved. Most organisations have a high level strategy, very few have a pragmatic plan for the next 1 to 2 years describing exactly what will be done towards achieving the overall strategy in that timeframe. Developing this practical implementation plan (still at a reasonably high level) is difficult work for the executives involved. However, once the plan is agreed it becomes the key tool for implementing effective portfolio management decision making to select the projects and programs that contribute most strategic value. Building this capability is a key governance issue!

The next key message is that developing the ‘road map’ and then accepting portfolio investment decisions based on the ‘road map’ requires discipline and cannot occur without strong executive level support. Manager’s ‘pet projects’ are always an issue!

One very useful idea was using the ‘road map’ and portfolio management to assess projects at the ‘idea’ stage – a standard one-page outline of the concept being proposed. If the concept fits into the ‘road map’ and looks feasible it is approved for developing a business case and planning, if it does not, it is rejected before much investment of time and effort has occurred. A much easier decision!! The process needs to be disciplined but not ridged – a degree of flexibility is essential to allow effective responses to market changes and regulatory changes.

The concept of value was also discussed – projects need to be assessed on their contribution to achieving strategic objectives as well as financial factors. Value is far more than just dollars!!

Probably the strongest message for me was the importance of concise information in modifying behaviours. An effective strategic PMO can have a huge effect on executive decision making simply by informing the executive of the ‘road map’ and of the effect any decision will have on the organisations overall journey towards its strategic objectives – good information really does lead to good decisions (and makes defending a ‘pet project’ very difficult – no one like to look too disruptive).

The importance of the routine aspects of portfolio management were not ignored (see more on portfolio management), understanding capability and capacity, the effect of queuing theory slowing everything down if too much work is approved was discussed, and the importance of effective surveillance of projects in progress were all covered. And my presentation on Portfolio governance and risk – its all about the stakeholders was well received.

A key closing thought is do not underestimate the time and effort needed to change organisational culture to facilitate effective strategic planning at the ‘road map’ level linked to portfolio management and the creation of an effective strategic PMO. Most presenters had spent 3 to 5 years building the capability within their organisations and were still working on the executive ‘culture’ to achieve the outcomes they were describing. The good news is that it is worth the effort; the SAP presentation quoted data showing an increase in profit of between 2% and 5% of the organisations turnover associated with implementing effective portfolio governance.